Not a Better World, Just a Different One

Vents Vīnbergs

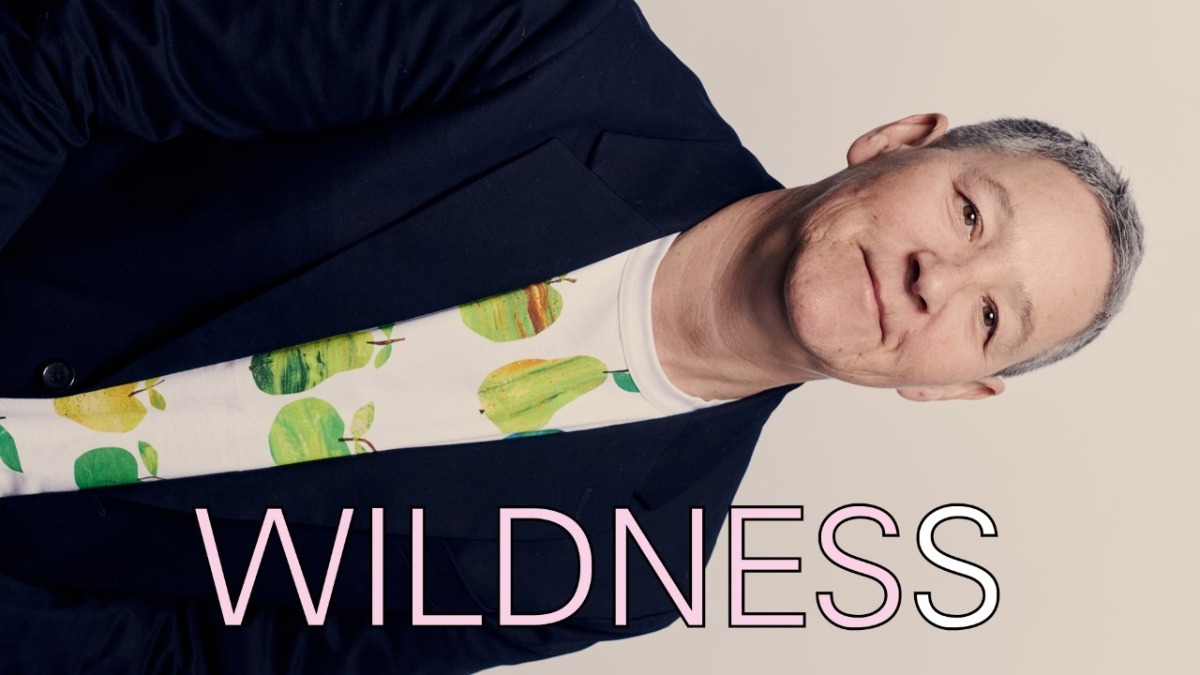

On Jack Halberstam, one of today's most prominent gender and queer theorists

As I perused my archive of notes, I noticed that I had returned to Jack Halberstam's (1961) texts as a kind of anchor from time to time, for almost a decade, but especially since I encountered his most famous book, Queer Art of Failure (2011). The title alone is an encouragement, but the ideas and various examples of queer life and art that it contains are a testament to the fact that my intuitive suspicion of everything that is considered success and normality in today's world has some basis. Or rather, I turn to Halberstam every time I need to remind myself that I shouldn’t castigate, but congratulate myself on both not conforming to the expectations of others and not fitting into the imaginary majority.

First and foremost, much of my constant tension is dissipated by his criticism of the notion of family and the "other half". The idea that finding a partner and living together as a couple is the norm and a success, while being alone is a failure and practicing other forms of social intimacy is a deviance, infects not only the majority of society but most gays, myself included.

This idea, along with other general norms of politeness and obedience, is absorbed in the family from parents and other relatives, taught in schools, broadcast in the media, and the pressure to find a partner is often maintained even by the circle of your closest friends and peers as a marker of success or failure in life. LGBTQ activists too have taken up the legal recognition of same-sex partnerships as their banner, hoping to meet, and be included in, the majority norm.

To Halberstam, this strategy seems absurd. Attempts at integration, to him, seems to be violence against oneself, and no less violent tend to be others' efforts to be inclusive, just as the state imperative to regulate this inclusion and capitalism’s – to make it profitable. In addition to the fact that queerness, otherness and non-inclusion are a value in themselves and that non-compliance can be an important political tool, he reminds us that the institution of marriage has failed, as has the social order that upholds it, and that the 21st-century’s gay movement’s attempts to defend it are essentially a renunciation of the radically different possibility of society that queer life has always offered. (The same is often said by another queer icon I admire, Fran Lebowitz – that the prohibition of marriage, or the freedom not to submit to such rules of society, used to be one of the biggest bonuses of gay life. So, the right to marry is a fight to preserve this historical form of slavery.)

According to Halberstam, the anarchy potential offered by gay lifestyle practices is not the same as libertarianism, or the focus on one's own private interests, and thus the demand to end state interference in their implementation. Furthermore, the denial of the institution of marriage does not automatically make people lonely and isolated. Getting rid of the constant frustration about an inability to create a normative couple and family opens up possibilities for other forms of cohabitation and togetherness, both enjoyable short-term ones and solidarity-based long-term ones – as flexible, changeable and unregulated as life itself really is.

Halberstam does not construct a utopian or better society (because "improving" in the modern sense actually means "making it marketable"), but in his works he constantly highlights examples of different lives that have always existed somewhere and that, despite the totalitarianism created by the idea of profit and rational action, are possible even now.

“I believe in low theory, in popular places, in the small, the inconsequential, the anti-monumental, the micro, the irrelevant; I believe in making a difference by thinking little thoughts and sharing them widely. I seek to provoke, annoy, bother, irritate, and amuse; I am chasing small projects, micro-politics, hunches, whims, fancies.”

That is why the concept of wildness has been appearing as a refrain in Halberstam's texts and presentations for some time. He began to think about it precisely in connection with the above-mentioned tendency, seeing how Queerness was ceasing to be a form of dissent and resistance, and that queer activism had begun to succumb to the pressure of normalcy and the regulation and commercialization of all walks of life. He seeks to change the generally accepted interpretation of wildness, which is that, in the modern world, everything that is contrary to civilization is therefore either expelled or "re-arranged" by colonization. If queerness no longer means either protest or otherness, but certain categories of legislation or just a little diversity of assortment in the catalogue of foreseeable lives, then the potential for freedom lies in everything that is unpredictable and uncontrollable, hence wildness.

This is an extremely timely thought, because in the post-industrial age and the unpredictability of current technological progress, everyone is subject to uncertainty and the collapse of normal life scenarios, not just queers. That will be the subject of Halberstam's next book, Wild Things. The Disorder of Desire (Autumn 2020). In it, he continues his favorite practice – not to speculate on possible alternative lives but to reveal that they have already happened and continue to take place somewhere.

Halberstam sees such a wildness, one that is not subject to generally accepted and governmental rules of procedure, in art. A large chapter in the upcoming book is devoted to the scandal caused by the premiere of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in Paris. Although this case has long been recorded in the canon of high culture and normalized, Halberstam recalls its wild and revolutionary nature, or the opportunity for Stravinsky to look into the savage that lurks below the veneer of civilization or notional order.

"My music is best understood by children and animals," Stravinsky himself later said no less rebelliously. In fact, it was childishness that Adorno accused him of, or simply anything contrary to the expectations of a sophisticated public, or, an understanding of harmony and symmetry. Children, on the other hand, are unfamiliar with these categories until they are trained into them. (Halberstam's readers will at this point be reminded of parallels with his earlier research, the narrative of the "childish", socialist uprisings that have found a home in lucrative mainstream Pixar cartoons, about weirdo outcasts who struggle to fight against the system, various beasts who unite in a common struggle, or a post-apocalyptic robot that throws a diamond into the rubbish but keeps the box because it’s more useful.) Halberstam also sees the rebellious wildness of the premiere of The Rite of Spring in its uniqueness – no records of Nijinsky’s choreography have survived (it’s possible that there weren’t any to begin with!), and all subsequent attempts at interpretation and reconstruction are a whole new world that this unique act of savagery gave rise to. The initial inability of the public to categorize this work of art, or to know what to do with it, is a feeling that Halberstam seeks to engage with again and again.

Furthermore, he recommends that such unpredictability be practiced as a principle of life.

I may have created a misconception about Halberstam when I said he gave me a sense of salvation and comfort. On the contrary, he inspires dissatisfaction with the usual order of things and learned life scenarios. Once I was envious of all those Eastern Europeans in Budapest, Belgrade and elsewhere who had been able to invite Halberstam to speak, inferring that there too was fertile ground for such underground otherness. But no, it’s possible everywhere, and now there’s an opportunity to meet Halberstam – albeit still remotely – also for the people of Riga.

Jack Halberstam's lecture “Wild Things: An aesthetics of bewilderment” took place on August 21, 2020 as part of a series of online lectures and talks organized by RIBOCA2.