Reconnecting to the vegetal mindfulness in us

Una Meistere

An interview with philosopher Michael Marder

Michael Marder is a Russian-born, New York-educated and currently Iberian-based philosopher whose work spans the fields of environmental philosophy and ecological thought, political theory and phenomenology. He is the Ikerbasque Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) in Vitoria-Gasteiz and the author of fifteen books and more than one hundred academic articles. Among these are Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life (2013), The Philosopher’s Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium (2014), Through Vegetal Being (2016), Energy Dreams: Of Actuality (2017), “What Needs to Change in our Thinking about Climate Change (and about Thinking)” (2020), “Should Plants Have Rights?” (2016) and “Is it Ethical to Eat Plants?” (2013). Together with the French artist Anaïs Tondeur he created the book The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness (2016), which centres on the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl on April 26, 1986, which also left a deep mark on Marder’s own life. At the time, he was six years old and, due to his severe seasonal allergies, was on a train with his parents to spend a few weeks in the Black Sea resort town of Anapa, unaware that it, too, would very soon receive radioactive fallout from Chernobyl, like most of the rest of Europe. “What exploded in Chernobyl was more than a nuclear reactor,” writes Marder, who today strongly advocates against the use of nuclear power.

Marder’s work focuses on changing the paradigm of humanity’s relationship with plants and non-human beings as well as the significance of the vegetal for our lives and for the future of the whole planet. Thus, he encourages a discussion about a more universal way of becoming human that is embedded in the vegetal world.

On June 18, Marder participated in the RIBOCA 2 online lecture and conversation series with “To Heal a Shipwrecked World: St. Hildegard’s Cures”. This conversation with him took place a week earlier, on Skype.

In your work, you speak a lot about vegetal and human mindfulness within us. It’s a very interesting point. Did you discover vegetal mindfulness in yourself as well, and do you understand what plants think?

Just to make things a little simpler, I tend to read the psychoanalytic ‘unconscious’ in terms of vegetal mindfulness. ‘The unconscious’ is not a negative non-conscious experience but a consciousness of another level than the one we tend to associate with the human. A part of my work is, indeed, an attempt at vegetalising psychoanalysis. After following Freud, one can do self-analysis, a psychoanalysis of oneself – and, to as certain extent I try to do it in a vegetal key, following a vegetal way of being. What it means is that this sort of vegetal mindfulness in oneself is very embodied; it’s a kind of temporality that we very often do not discern with our limited perceptual apparatus, because time can flow much slower than the changes that we can register on our conscious radars. That other rhythm or other pace of temporality, which is much slower, is vegetal consciousness.

It’s also much more superficial than what we tend to think of as the interiority of psychic life. In that sense, I really differ from Freud, because Freud developed the structures of unconscious depth and depth-analysis, which is another name for ‘psychoanalysis’. I think that, if anything, vegetal consciousness resides on the surface and we simply do not notice it. It’s so much a part of ourselves, so integral to our lives that we no longer pay attention to it. It’s almost like skin – both bodily skin and the psychic skin. Here, psychological and physiological phenomena are almost inseparable from one another.

The skin is, thus, the most vegetal of our organs, the most superficial, at once psychological and physiological.

One example is when we think about spirit or the psyche as a mode of breathing. This connection of the soul to breath is very old; it goes back to both ancient Greek philosophy and the Hebrew Bible as well, where the word for ‘spirit’ or ‘soul’ is ‘breath’. We tend to think about the lungs as the organ of breathing, and although the lungs are an internal organ, they expose us to the exteriority of the atmosphere. Some philosophers, including Hegel, consider the lungs to be analogous to a leaf in the human bodily constitution. But the lungs are not the end of the story of breathing, because we also breathe through our skin, which, with its pores, is a breathable surface par excellence. In that sense, it’s perhaps even more vegetal, giving us the sense that we’re wrapped within a leaf. The skin is, thus, the most vegetal of our organs, the most superficial, at once psychological and physiological.

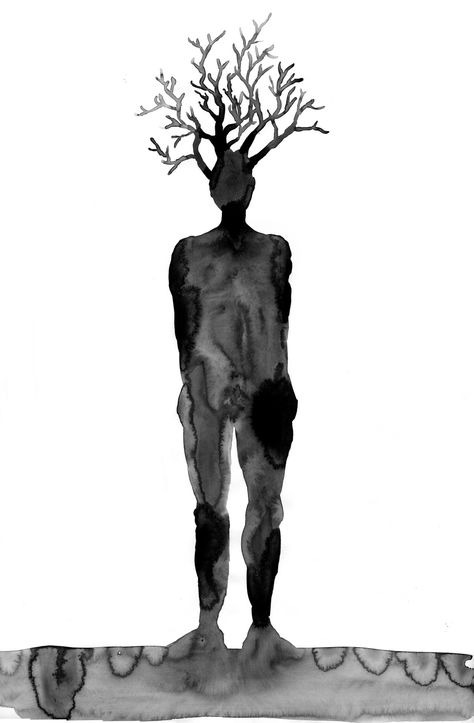

The drawing by Mathilde Roussel for Michael Marder's book "The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium" (2014)

But do you think it’s possible for a human to understand what it is to be a plant?

I would like to put this question in the context provided by the history of Western culture and philosophy, in alignment with psychoanalytic discoveries. There has been a tremendous psychic investment in repressing a vegetal layer of human existence. So, if there’s anything really repressed in us, it’s our vegetality. I feel it’s my task, in a very modest way, to try to lift some of those barriers of repression. To unrepress the plant in us. To let something of the vegetal in us shine forth and express itself.

When we see an unbridgeable distance between us and the plants, that very vision of the distance is already a product of centuries and millennia of cultural repression. But even in the history of Western philosophy, there are insights into the fact that there’s something vegetal about the human psychic constitution. Aristotle thought that the most basic level of the psyche is vegetal. It’s the most shared, the most fundamental mode of life, common to all living beings whether they’re plants, animals or humans, the level that’s responsible for these beings’ nourishment and reproduction. The whole structure of the Aristotelian soul is built upon this principle of vegetal vitality as its base.

And then, obviously, we can ask: are the other levels that we associate with animality and humanity merely superimposed upon this base, as in the mineral world, where the upper layers rest upon but are ultimately separate from the foundations, or (and this is the hypothesis that I like and that I develop in my work) is it that the rest of the psychic edifice develops by way of sublimation, a transformation, at the same time, one could even say a perversion, of the foundation? I see continuity, an emanation of the so-called higher levels of consciousness from this basic shared level, never a really drastic, significant cut between them. And, in that sense, the cut that appears to us as an absolute unbreachable gap between us and the plants is more the product of a cultural framework that has been imposed upon us for millennia.

The drawing by Mathilde Roussel for Michael Marder's book "The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium" (2014)

There’s a theory that the development of language marked the moment when humans separated from nature and the plant world. We lost our sensibility and understanding of nature because we started to build our world on text. Do you agree?

It depends on what we mean by language. If by language we mean the spoken word, without even referring to writing, to my mind this is only a limit case of what language is. If, beyond vocalisation, language has another function as a means of expression, then all plants, animals and living things have a kind of language because they all do express themselves, even spatially, by assuming particular postures or positions. In the human world, body language is considered a kind of language even though it’s not spoken; one can articulate what one expresses – often unbeknownst to oneself and also unconsciously – through bodily positions and gestures. I would go so far as to say that we share this language with plants, because what they are and what they express is one and the same in their self-organisation and in their articulation of their body parts. Plant have perfected body language, not least because they can lose virtually any one of their parts and regrow and reconfigure themselves according to the different seasons or their physiological needs and so on. Once again, my hypothesis would apply here: what we call language, identifying it with a purely human language, is a kind of sublimation, a productive perversion of those other unconscious and non-human modes of expression that we do not typically associate with linguistic expression.

Your research projects are also in a way autobiographical. For example, as a child you suffered from seasonal allergies caused by pollution. You reflect on that condition in Through Vegetal Being and The Chernobyl Herbarium, mentioning that physical allergies are more or less reflections or direct consequences of what you call the metaphysical allergy of Western philosophy towards the plant world and the environment as a whole.

Yes. I insist that Western metaphysics or Western philosophy is not just a collection of obscure doctrines that are gathering dust somewhere in a library. They have very real, concrete effects – ongoing effects that we cannot really escape from. In my more recent work (the forthcoming book Dump Philosophy: a Phenomenology of Devastation), which is not so much on the philosophy of plant life, I consider non-decomposable materials with which the world is filled (plastic, depleted uranium, etc.) as strange, nightmarish realisations of metaphysical dreams, the dreams about immutable existence that philosophers at least since Plato have been yearning for. And now, finally, in the 20th and 21st centuries, such dreams have been realised in a nightmarish way through the production of materials that are non-decomposable, such as depleted uranium, which takes hundreds of thousands of years to degrade.

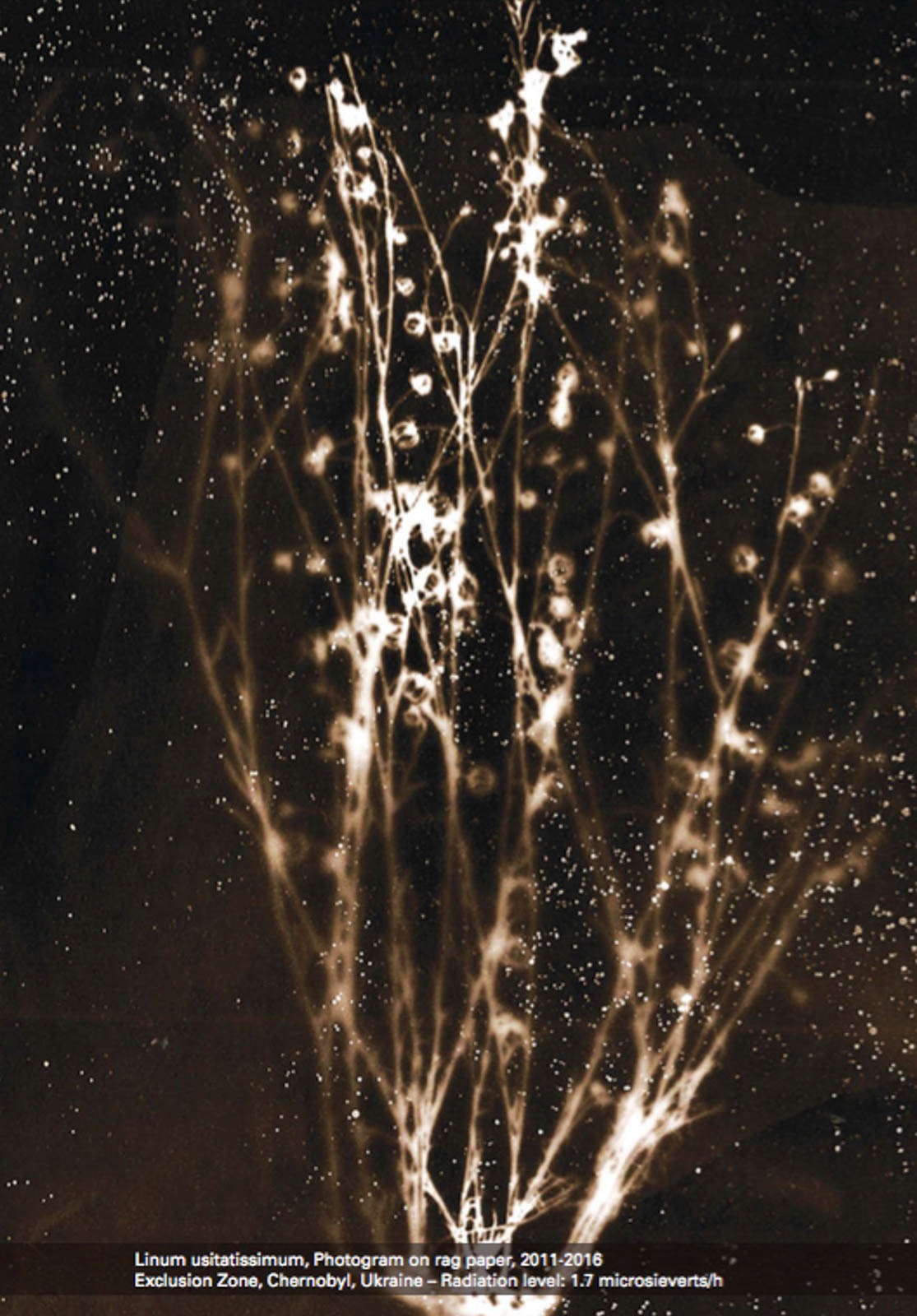

The rayogram by Anaïs Tondeur for Michael Marder's book "The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness" (2016)

Although it appears to be very abstract, philosophy produces concrete effects in the world, and that’s why I link “seasonal” physiological allergies and Western philosophy’s metaphysical allergy to plants. A culturally specific, historical separation of humanity from our natural surroundings accelerated with the movement of urbanisation and the creation of more artificial environments, realising in fact the ideal separation that was envisioned and celebrated by philosophers. After all, physiological allergies are provoked mostly by heavy industrial pollution and the use of disinfectant materials that simply do not allow our immune systems to train themselves in recognising what is harmful and what is not. Our obsession with cleanliness leads to lots of problems and actually to an increase in environmental pollution, as is finally becoming obvious in the current Covid-19 crisis. All of that results in a situation where the metaphysical allergy to plants does not just mirror a physiological allergy but, through circuitous routes, triggers it, rendering it widespread.

I insist that Western metaphysics or Western philosophy is not just a collection of obscure doctrines that are gathering dust somewhere in a library. They have very real, concrete effects – ongoing effects that we cannot really escape from.

When we speak about nature, we humans always separate ourselves from it – there’s ‘it’ and ‘us’. Why is it difficult for us to accept that we’re part of nature?

It depends on how the nature that we’re separated from is framed. Very often, a purely natural world is associated with plants in particular, with the wildlife that is primarily vegetal. We know that the emergence of larger-scale human societies is linked to agriculture, in which there’s a drastic reduction in the scope of vegetal life that’s cared for and cultivated by humans. Although at first it does not involve monoculture, with the cultivation of crops comes standardisation, a mutual furnishing of uniformity between human societies and what remains of nature. Everything that’s heterogeneous, everything that contains diversity and difference in uncultivated nature, we distance ourselves from it. We see a source of threat in it, as it were. Especially, if we compare this ideally uniform and easy-to-survey agricultural milieu with a forest.

The forest is, obviously, a matrix for the development of central and northern European societies, which had to somehow win space from that ecosystem. Such societies had to emerge, in a sense, in opposition to the forest. Here, the forest stands not just for a particular ecosystem, but for the uncontrollable, for the wildly proliferating that cannot be rendered uniform as a cultivated field can be in the creating of monocultures. The opposition between the forest and the field, to my mind, is also in a sense a metaphysical opposition, a self-perpetuating vicious cycle of yearning for more and more ideal uniformity both within human society and outside it, and seeing everything that’s heterogeneous as a source of threat, associated with “wild” nature.

Speaking from the situation we’re now in regarding the Covid-19 pandemic, at the start of it the internet was saturated with images that had not been seen for ages: clear skies above Delhi, views of the Himalayas from Kathmandu, clean air in central Moscow and so on. But now, when things are seemingly getting back to normal in Latvia and elsewhere, there’s a feeling that people are ready to adapt to worse conditions just to get back to how things were, and they’re forgetting about things like the appearance of clear water in the canals of Venice and so on. In other words, no lessons have been learned. Apparently, Covid-19 is too mild to have brought about real change.

I agree to a certain extent. Some hold the theory that the new coronavirus, responsible for Covid-19, is the return of repressed nature. But it’s not pure nature. There’s impurity in the original virus itself, because it jumps species (it passes from other animals to humans) – and, obviously, it would not have spread so successfully from the standpoint of the virus itself were it not for the technological and cultural conditions of globalisation. I see it as an exemplary mix of culture and nature. That said, in a state of the suspension of business as usual (industrial activity and transport), we experience a clearing of the skies, improvements in the atmosphere and waterways, but that does not mean that other modes of pollution were not intensifying. Think about all of the personal protective equipment that’s not recyclable and that’s going to create a huge problem in the long term as it accumulates en masse. Not to mention, the flood of disinfectants that has been released into the environment.

The other point that I want to make is that it seems to us that there’s a suspension of the capitalist machinery when we’re not consuming, when factories stop, when flights are cancelled… We assume that both production and consumption cease if sufficiently great numbers of us do not participate in these spheres. But something weird happens in late capitalism: in an eery anticipation of total automation, the economic machine can run also without human producers and consumers. Take the example of the extraction of oil. Planes were not flying during the lockdown, and there’s been less demand for oil than before across the board, but that does not mean that the production or the extraction of oil has diminished. It was being maintained at more or less the same level, and, when possible, the excess was being stored. Once storage capacity is no longer adequate, however, there’s a horrible practice of “flaring” in the oil extraction industry: they simply burn off excess oil or natural gas. In other words, the emissions were still released into the atmosphere, just not in the usual places. They were not as spread out as usual, given the traffic routes of airplanes; instead, they was much more hidden, like the other kinds of pollution that happened as a result of Covid-19. It’s a crazy, deranged machinery, this latest incarnation of late capitalism that runs on its own even without human producers and consumers. So, I’m much more pessimistic in that sense, and I am critical of attempts to discover redemptive environmental aspects in Covid-19.

Something weird happens in late capitalism: in an eery anticipation of total automation, the economic machine can run also without human producers and consumers.

So, in some sense, we’ve reached the point of no return?

Yes. In some sense, yes. But this point does not coincide with an external shocking event, such as Covid-19. We live in a culture of the end, which has put an end to many worlds. The loss of biodiversity, as much as of cultural and linguistic diversity, signifies the ends of worlds (a double plural) rather than ‘the end of the world’, on which Western culture is actually predicated. Western culture has been expecting and quickening the end of the world since its inception [chuckles]! We’ve come to expect these catastrophic cataclysms/events as triggers for change. But I’m not sure to what extent this can really work, because it’s all too easy to believe that a more or less accidental external event will suddenly change how we think. On the contrary, the work has to be much more long-term, patient and deep – work, through which we change our thinking, the way we organise politically, the way we develop the economy based on a conscious effort of reconnecting to our vegetal unconscious, to the vegetal mindfulness in us.

I advocate this much more patient, long-term work as opposed to celebrating sudden catastrophic trigger events that, as you yourself mentioned, may produce a rather superficial short-term change but then make us delve back into routine precisely because there has not been any groundwork of preparing what should be done in order to make change viable and lasting.

We recently had an interview with American geophilosopher David Abram, and from his viewpoint the age of the Anthropocene is already over. He thinks the right name for this new epoch should be the Humilicene, from the word ‘humility’. The era of humbleness. Do you agree?

I wonder to what extent the Humilicene is just a part of the Anthropocene, because it still bets on humbleness as a very human kind of feature. There are many qualities that have been considered purely human but that we now find in the animal world as well, but humbleness seems to be one of these highly refined human attitudes. More than that, when I find myself in a Nietzschean mood, it seems to me that the professions of humbleness and absolute love of all creatures can hide a very reactive attitude, a masked hatred of the world, as Nietzsche would say. That a new love of the world has been found in or after the Anthropocene is a finessing of a deeper, unconscious feeling, which is the exact opposite of it. That could be the case, and that’s why I’m still very faithful in my own way to the legacy of psychoanalysis and to trying to find the deep roots, the unconscious roots of affect, that obscure stratum of the unarticulated, on which every articulation grounds itself.

The drawing by Mathilde Roussel for Michael Marder's book "The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium" (2014)

Returning to plants, you were looking into the attention process of plants. What did you discover? How does it differ from that of humans?

It’s true that about ten years ago I wrote several articles for a plant science journal in which I tried to imagine a theoretical framework for thinking about issues related to plant intelligence. With respect to those issues I wrote about attention: in what ways do plants pay attention? Here I relied very much on the phenomenological framework of consciousness that [Edmund] Husserl calls intentionality. Not intentionality in the sense of having intentions to do this or that, but, rather, intending as directing oneself toward a target or an aim.

I found out that plants are exquisitely attentive and intentional, or intentive, because they direct themselves in multiple directions at once. Their lives span various milieus: they live below ground through their roots and above ground through their branches, leaves, flowers... Their intentionality, their attention is hyper-attentive movement, which is not, to my mind, centralised – it’s not concentrated on a single object as human attention tends to be, but is dispersed and turned toward everything and everyone the plant finds outside itself.

Again, a parallel in human life could be our distracted attention in the condition of late modernity, when there are so many demands and things vying for our attention. We’re becoming much more vegetal in that sense, too. No one works towards a certain task, completes it and then moves on to the next task anymore. This model of behaviour that has been practically questioned and has become almost outdated. Multi-tasking is our variation on the theme of vegetal attending that is excessive and relies very heavily on the margins of the field of attention, the boundary regions between conscious and unconscious processes. Instead of focusing our attention on a conscious point upon which we concentrate, we work more around this margin or boundary, attending in a hyper-attentive way to too many things at once and, therefore, operating in a distracted mode of attention. I think that this is also the way plants attend to the world.

Plant scientists know that plants are aware of at least twenty environmental conditions, and they attend to all of them at once. If we take into account the different combinations of these factors, then to translate them into algorithms is a very complicated way of attending to the world. This juggling of many different aspects of the environment – not through a single command-and-control organ, such as the brain or central nervous system, but in every part of the plant, in every leaf, at every root tip – means that there’s an apparatus for attending, which is dispersed and which perhaps integrates itself occasionally, but without a single structure that would unify it into a coherent whole.

In some of your work you draw parallels between plant life and art – you’ve done many projects that are on the borderline between philosophy and art. What do plants have in common with art?

Plants have a lot in common with the artistic process, but I would highlight in this context the performativity of plants. Plants constantly create and recreate themselves; they’re the performers of their own existence. They’re never static, even though they seem to us to be immobile. As I’ve already mentioned, their bodily organisation is changeable, malleable. The simplest example: they lose their leaves in autumn and grow new ones in spring, sometimes along with detachable sex organs, the flowers. This kind of self-rearrangement is a crafting of themselves that I would associate with a performative, artistic function.

Plants have a lot in common with the artistic process. Plants constantly create and recreate themselves; they’re the performers of their own existence.

But there’s also an interesting feedback loop in how plants shape their world – that is, the world of the elements, where they create microclimates and contribute to the atmosphere and the composition of the soil, even as they are shaped by those very conditions. It’s a feedback loop, in which I see not just an ecological process but a moulding that goes beyond the distinction that used to exist between activity and passivity. In this way, plants poetically create their world and are in turn created by it.

For several years you spent almost every weekend alternating between the works of art inside and the woods around a gallery in Ontario. What did you learn from that exercise?

The work of human artists gain a different significance and meaning once it’s framed in a setting that’s distinct from the traditional museum or gallery. There is a trend that has been going on for decades, both in philosophy and the art world, of questioning the distinction between the inside and the outside. The inside and the outside of a museum, for instance. The outside, the natural surroundings and woods around a gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario you mention, were for me as much a work of art as what was inside the gallery. There was a constant dialogue I believe I was witnessing between the works by the “Group of Seven” Canadian artists and the gallery’s setting. The surroundings moved from the margin to the centre and then receded back to the margin only to move to the centre again. This difference that you’re referring to – the fact that the place looked different each time – was precisely thanks to the unsettling of the usual balance between the figure and the background, the centre and the margin. The movement could go on almost indefinitely, with the two elements changing places…

I found your book The Chernobyl Herbarium, written together with the wonderful artist Anaïs Tondeur, really powerful because of the way it put together these two parallel worlds – amazing art and a text that is also deeply personal.

This was the first collaborative project that Anaïs and I carried out, and our work together is continuing. The book that I referred to previously – Dump Philosophy: a Phenomenology of Devastation – is another one of our projects, which is coming out later this year. We’re also continuing to work with the issues of plant life, specifically reflecting about not only the content and form of the philosophy and art, but also the method. This might be a great opportunity to rethink how philosophers and artists work together without generalising any rules of the game, but starting from the subject matter at hand, in this case, plants. It is a matter of showing the different ways in which we can respond to and learn from plants and correspond with one another based on that mutual learning experience. In the new project we’re contemplating now, it’s very much the question of method that preoccupies us, in that we would try to follow plants in the unfolding of the work itself. How is it that art can grow out of philosophy and philosophy out of art – symbiotically, mutually – while keeping close to the process of vegetal growth?

The rayogram by Anaïs Tondeur for Michael Marder's book "The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness" (2016)

You write: “Animals and plants are returning to the Chernobyl restricted zone because the human beings are now gone, not because the soil is more fertile. We could celebrate this turn of events, finding in it a kind of laboratory for a vibrant planet that would survive the human onslaught long after our species is extinct.”

In this passage I also questioned the sustainability of the return, because it has been very much idealised. I see lots of parallels between the situation of Chernobyl and Covid-19, where, presumably, it’s enough for humans to physically withdraw from the picture for everything to get better and for nature to regenerate and reinvent itself. But things are not as simple as that, because what happens in the Anthropocene is that the physical presence of human beings and activities no longer matters. Even when we’re out of the picture, that presence continues at a subterranean level, because the mark of all of these horrible emissions has been left on the crusts of the earth, in the oceans, in the atmosphere. Geologically speaking, that’s something that will remain in the fossil record and will testify to our presence even after the actual representatives of Homo sapiens are long gone. The same goes for Covid-19 and the withdrawal of human industry, as well as the situation of Chernobyl, because it’s not enough for humans to withdraw when the soil and everything else for that matter has been contaminated by radioactive waste.

The rayogram by Anaïs Tondeur for Michael Marder's book "The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness" (2016)

What I emphasised in the passage you cite is that one of the effects of radioactivity is that it interfered with the very fragile communities of decomposers – fungi, bacteria and others that live in the soil and actually perform the work of “metabolising” vegetal and animal matter and renewing the soil. Because radiation has negatively affected the communities of those decomposers, plant matter is not rotting as it should. It keeps accumulating on the forest floor without renewing it. That, in turn, leads to forest fires. At the same time as the Covid-19 crisis was worsening in Europe, there were tremendous forest fires in the Chernobyl area, which were underreported in the Western media because all of the focus was on Covid-19. The fires actually came very close to the damaged reactor and the situation was getting extremely dangerous. So much dry vegetal matter has accumulated on the forest floor over the last thirty-plus years that it’s providing plenty of fuel for such fires. The return of the wildlife may be a short-lived one if the soil does not recover its regenerative capacity: Chernobyl will be barren in a few decades.

Photo by Michael Marder

Regarding biological heritage and collective memory, what do you think about the controversial hypothesis of morphic resonance proposed by Rupert Sheldrake – that “memory is inherent in nature” and that “natural systems [...] inherit a collective memory from all previous things of their kind”?

I agree with this hypothesis to a degree. I’ve written about vegetal memory, arguing that plants have memories at many levels. Again, like their language, their most obvious memory is spatialised – it’s a spatial archive. If you look at the cross-cut of a tree and the rings that correspond to years, you can very much see the nourishment a plant received in a certain year. So, there’s a spatial archive in the very body of the plant. Also, at the molecular level, leaves and other parts of plants obviously have memories, and they use those memories to act in various situations.

To give an example, a plant must make a decision on the best time for blossoming. For trees, this is a life-or-death decision, because the temperature and other conditions have to be just right for their huge energetic investment to literally yield fruit. To make that decision, a plant constantly monitors the changing conditions in its environment. For instance, the differences in temperatures from one day to the next, the increasing length of daylight, etc. Leaves have a memory of the last rays of the sun, which have a unique wavelength range. They remember when those last rays of the sun hit them, and they collect such memories for a period of, say, thirty days. They then compare the differentials among them, combined with many other factors, to asses when the best time to blossom would be. In that sense, memory is not just a passive archive but a guide to action for the plants.

We could say that just about everything that surrounds us is a kind of externalisation, or embodiment, of memory. A well-known mnemonic technique is to associate one thought with one thing in one’s immediate environment, so that this thing, when perceived, would then trigger the memory. I take this technique further: besides a more interior picture-memory, you could say that our very physiology, our embodiment, is a kind of memory. Like the trees, we are an archive of what we eat, for instance. With a little bit of effort, we can discover vegetal remembrance in ourselves.

Photo by Michael Marder

Have you seen the Italian film La Grande Bouffe by Marco Ferreri? It’s about three hedonistic men who decide to gorge themselves to death on fine cuisine. It came to mind when I read your article “Is it Ethical to Eat Plants?” Eating is a part of our culture – in France, for example, eating is part of the cultural canon. You seem to have a different viewpoint. Is gastronomy a part of culture or not?

Eating definitely is a part of culture, and it’s a part of the economy, as well. For all “ethical” agricultural products to be available, the economy has to be organised in a certain way. Especially in the American context, for which this paper was written, it’s important to emphasise that individual choices are important and significant, but one should not lose sight of the other, again, contextual factors, such as the cultural and the economic, that make possible (or impossible) the ethical choices about what one eats and how. In order to envision something like ethical eating (which is not a fully attainable goal), there has to be a concerted transformation in multiple domains at the same time, not just a radical individual choice one makes after a moment of sudden enlightenment (I’m, of course, making a caricature here). There needs to be a transformation of cultural frameworks, which usually happens very slowly – cultural transformations are some of the slowest – but also a transformation of the economy, in which one moves away from an agrobusiness/agrocapitalist economic mode to a much more ethical organisation for all involved: plants, humans, animals, the elements… Right now, with organic agriculture and so on, what we see are pockets of what is possible, but these pockets of transformation are framed ad and become market niches for those who can afford them. Again, this makes individual choice quite meaningless if one does not have the financial resources to eat ethically.

Like the trees, we are an archive of what we eat, for instance. With a little bit of effort, we can discover vegetal remembrance in ourselves.

Another important point is that disrespect toward one kind of living beings usually goes hand in hand with disrespect toward others – and again, I’m responding mainly to my American interlocutors. I mean, it’s not enough to just say, “I’m absolutely going to cherish humans and animals but I will do whatever I please to plants and I will consume them in whichever way possible.” The acceptance of a lack of limitations in the treatment of some living beings, regardless of what or who those other living beings are, is already a problem that will make ethical action and eating unviable. At the extreme, it’s impossible to have a purely ethical action, a purely ethical way of eating, because someone or something will always get harmed. But we can try to minimise those harms. The worst thing is for a person to think that they can embody the purity of acting and eating, to the point of becoming a standard, a model for all others to emulate. Both individual and organised violence (and the economy is also an organised form of violence in how it produces beings) usually traps the perpetrators in a vicious circle together with whomever is being violated.

Photo by Michael Marder

We are what we eat, as you said. Is what we eat a physical reflection of what we think?

It goes both ways. I’m mostly thinking about Nietzsche and his attempt to develop a psychology based on physiology, including the crudest of physiological processes. He goes back (even though he does not acknowledge it) to Aristotle and the vegetative soul, which is the principle of vitality based on nourishment and reproduction. When one says, “Let’s make physiology the basis for psychology,” as Nietzsche also does, it means that one is ready to take into account the vegetal processes in us as the material foundation for what seem to be very abstract ideas and modes of thinking. I go back to my earlier point: our so-called highest pursuits of abstraction (abstract thinking, art, etc.) are the sublimated and no longer recognisable transformations in that material physiological foundation, which is vegetal.

Have you found an answer for yourself to Heidegger’s question of why are there beings at all, instead of nothing?

I dare not to actually raise this question because I work in a phenomenological tradition, which should have limited Heidegger’s scope, too. I prefer not to question why but rather how [chuckles]. And so, I see in phenomenology a commitment to moving toward the surface of things, almost gliding on their surfaces and therefore (despite everything we can learn from depth-psychology) being faithful to an essentially superficial way, in which plants exist. That is why, why is a question that’s too deep for my liking. One can find depths that are more meaningful on the surface, by asking the question how instead of why: how do beings exist? How do we and how could we exist? What are the possibilities and the actualities of existence?

Life and existence are always about being in the middle, and in that we are all like plants, because they have no clear origins or ends.

Another of Heidegger’s quotes that I like very much is: “What was Aristotle’s life? Well, the answer lay in a single sentence: ‘He was born, he thought, he died.’ And all the rest is pure anecdote.” Can we say that about humanity as well?

No, I don’t think one can say that about humanity. Above all, because the question of the death of humanity is very difficult to answer. The death of a single human being, obviously, but also the death of humanity, precisely because the effects one produces live on beyond one’s own life, be it the life of a person or the species. Something of a human life, whether individual or collective, is going to reverberate, spectrally haunt, and continue to return even after one is gone or after humanity as a species is gone. The question of beginnings and ends becomes tricky because such boundaries are never rigid. If anything, I think it’s the middle we should be concentrating on. Life and existence are always about being in the middle, and in that we are all like plants, because they have no clear origins or ends. Just proliferating middles. If you take the fruit of a plant to be its end, this fruit contains the seeds for a new beginning. In a way plants are very skilful in turning ends into beginnings and beginnings into ends. Instead of obsessing about clear-cut edges and distinctions, we should follow continuous lines – living and working and being in the middle. This is what I focus on in my work.

Thank you. That’s quite a beautiful ending for an interview.