Art as a spiritual practice: the meanings of mandala creation

Helēna Kārkliņa*

Spirituality can be understood differently among all individuals depending on cultural background and the specific context. Many associate it with a sensitivity and attachment to religious values, while others define spirituality as an ongoing process of self-reflection that helps to expand the meaning and purpose of one’s life.[1] The well-known intellectual and historian Yuval Noah Harari [2] states that “religion is a deal, whereas spirituality is a journey”. Common to most such interpretations and definitions, however, is the recognition of spirituality as a practice. Juris Rubenis, a former Latvian pastor and a writer, has compiled more than a hundred spiritual practices in his recent book and concluded that “creative practices are the broadest group of all spiritual practices”.[3] Now, art comes into play. Not only does art help to transmit different spiritual beliefs and values through symbolism and aesthetics, but the very process of creating art is loaded with symbolic meaning. The centrality of the creation process, rather than that of the finished art piece, gives new meanings to the relationships between art and individuals.

A mandala is a form of symmetrically arranged circular art that originated in Buddhism; it was later borrowed by other Eastern religions, then eventually transformed by different modern spiritual traditions. Traditionally, a mandala is understood as a symbol of the Universe or, for more abstract analysis, a symbol of completeness, and is used as a tool for focusing one’s attention during meditative states. The traditional approach is still maintained and actively practiced in countries such as Tibet, India, Nepal, Indonesia, and China.[4] Characteristic of all mandala art (both traditional and contemporary) is an emphasis on both the importance of the creation process and the careful analysis of the finished piece, since both of these aspects are believed to serve as tools of reflection. In this article, I will explore the meanings attributed to the contemporary mandala-creation practices as well as the ways in which these practices are understood as spiritual practices. For the purposes of gaining qualitative data for my anthropological studies, I have conducted interviews with three experienced representatives and seven mandala-art practitioners of various level in Latvia.

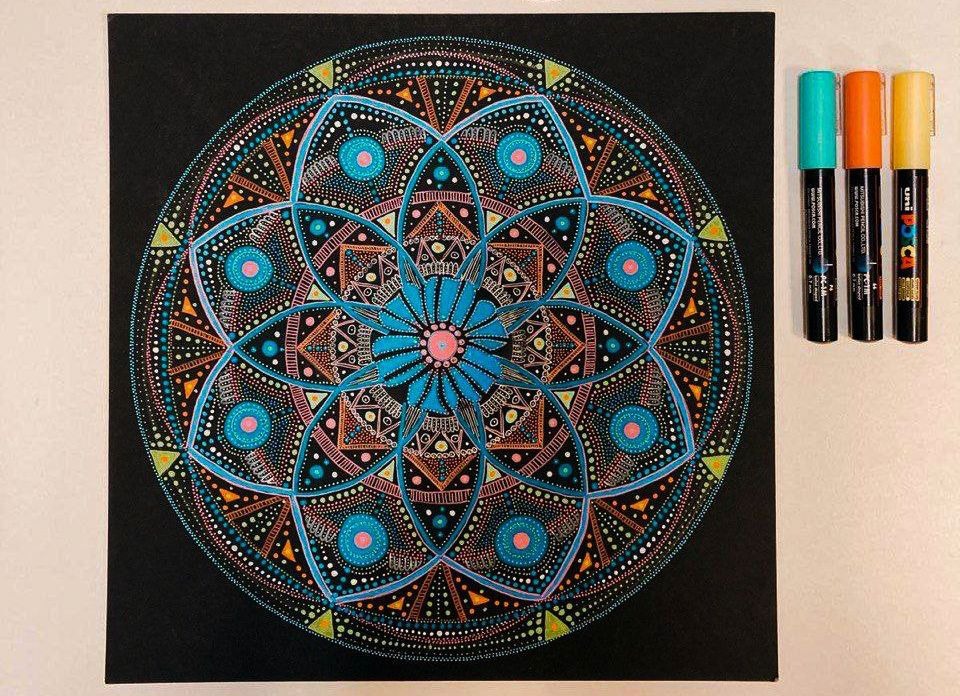

Foto: Vineta Liepājniece

UNDERSTANDING THE PRACTICE

It is necessary to look at contemporary mandala-creation practices separately from traditional ones not because they are incomparably different in their finished forms, but because of the distinct cultural and social contexts that surround these practices and, thus, transform their meaning and purpose. In their essence, all mandalas can be understood as carriers of symbols and complex meanings that can serve as introspective tools for any given narrative. In traditional mandala-creation practices, however, this narrative often regards external situations (symbols are used to give meanings to happenings of the external world and to learn concepts and history via visual communication), whereas contemporary mandala-creation practices focus on interpretation of subjective and internal processes. The rise of contemporary mandala-creation practices was initiated by the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung, who understood mandalas as practical tools for self-reflection, thus welcoming the possibility of secular mandala uses and interpretations.[5] Mandala-creation practices are generally recognized as self-reflective and spiritual practices among practitioners because of the two-part approach they offer: firstly, the creation of the mandala, and secondly, its thorough analysis (the translation). Each approach plays a different role, however it is the conjunction of these approaches that grants the contemporary mandala-creation practice a spiritual meaning.

Foto: Vineta Liepājniece

CREATING A MANDALA

There are many types of mandalas and mandala-creation methods, however, I will give a more comprehensive insight into the creation process and the meanings linked to it without focusing on the diverse characteristics of each method. The conversations I had with practitioners of contemporary mandala art revealed that the creation of a mandala is understood as an exercise of focus and creativity. Although the process of creating a mandala varies depending on the exact mandala type, the intention of it is to create intuitively, that is, without critical evaluation and without any particular expectations. Mandala artist Stephanie Smith explains that “when you focus on the process of art-making (...) over the quality of your efforts, you are beginning to practice mindfulness”.[6] There are, however, a set of rules one must follow when creating a mandala. These rules can be as simple as agreeing to a fixed starting point of the drawing (e.g., developing the mandala from its center outwards or, as in some cases, in the opposite direction), or as complex as implementing precise geometrical calculations in the layout of a mandala. Such rules are necessary for a proper analysis of the finished piece. The mandala type one chooses to create and, thus, which rules to follow, remains subjective and may vary from day to day.

When asked to describe the mandala-creation process in more detail, practitioners emphasized the need for a spiritual attitude and a ritual-like approach. First, this approach implies a particular state of mind that can primarily be characterized as the desire to create and the ability to concentrate solely on the practice. Many equate it with a form of meditation. Second, the physical and social environment must be taken into account for successful encouragement of the necessary mind states. One must prepare an undisturbable space and all the necessary tools in advance so that there are no disruptures in the creation process. Practitioners are encouraged to engage in this process either by themselves, that is, without the needless presence of others, or in groups of other mandala practitioners. When creating in groups or workshops, most interviewees reported an improved quality of practice, linking it to the sense of like-minded community as well as to a stronger sense of a ritualistic approach – the workshops provide the participants with a suitable environment (by providing a quiet space, all the necessary tools, and support). It is, then, the ritualistic approach that largely helps to create the space between daily life and artistic practice.[7]

Foto: Vineta Liepājniece

TRANSLATING A MANDALA

The analysis, more commonly referred to as the translation of a mandala, is as important an aspect of the mandala-creation practice as the very process of creation. Many of the emerging patterns of a mandala, such as geometrical figures, color placement, and the detailedness of the piece, have been ascribed with certain meanings. Therefore, a finished mandala, unique in its appearance, reveals pattern and color combinations that are understood as precise indicators of one’s character or conditions. However, among the mandala-creation community, the offered translations vary considerably – some practitioners apply narrow and straightforward translations to every shape and color (e.g., the color red in the center of a mandala indicates inflammation), while others draw conclusions based on the overall symmetry of a mandala (e.g., symmetry indicates balance and order). One practitioner stressed the central importance of one’s own interpretation – “You must first experience the process of creating a mandala. Then you analyze whether it helps you in any way, and if so, how? Only by making observations can you start to relate your mandalas to different circumstances, and then you are able to translate them in your favor. No one else should intervene in this process. No one should tell you the meaning of your finished piece but yourself”. In any case, while the creation of a mandala is understood as a meditative exercise, the purpose of mandala translation is that of self-reflection.

Before creating a mandala, most practitioners set an intention, that is, they put forward a question, a problem, or a narrative and translate the finished piece as a corresponding insight. Mandalas are then understood as not only carriers of symbols and meanings, as mentioned above, but as carriers of advice, too. Since practitioners have emphasized the impacts mandala creation and translation has had on their lives, it can be understood as a tool for consciously shaping one’s identity by one’s own initiative. Through the practice of mandala translation, all practitioners reported an improved sense of self-understanding which has then impacted their further decisions.

Foto: Vineta Liepājniece

MANDALAS AND SPIRITUALITY

As already mentioned above, it is the conjunction of the two approaches that grants a spiritual meaning to contemporary mandala-creation practices. I shall demonstrate this with a clear example. Among my interviewees were two practitioners who did not attribute any spiritual meaning to the mandala-creation practice. They described the process in simple terms, such as fun and calming, however, it is exactly these two interviewees who practiced creating mandalas without trying to translate them. For them, mandalas are just a form of creative expression, and moreover, a safe way of being creative since mandala creation doesn’t require any advanced artistic skills. On the other hand, all of the practitioners who practice both the creation and the translation of a mandala, despite the various approaches to such translation, either outrightly refer to this practice as a spiritual practice or express a spiritual attitude toward it. It was made clear by those who used the term “spirituality” that in this context, it is not tied to religious values (although this doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be) but to a holistic approach to life and a notion of exploring one’s purpose. Most of the practitioners describe this practice as, above all, transformational. Laura H. Campbell points out that “(...) art making and art inquiry encompass a variety of experiences involving a multitude of senses”.[8] Similarly, one of the interviewees suggested that “neither art nor spirituality can be objectively defined, therefore, no one can tell us that mandala-creation is something less than that [a spiritual practice]”. Gracia points to the human tendency inherent at all times and places to enquire oneself and the surrounding world and to synthesize the acquired knowledge “in a formula that [man] can transmit to others (...)”.[9] For regular practitioners, the mandala-creation practice represents this effort and, thus, is their chosen tool for such an inquiry.

Contemporary mandala-creation practices have acquired a dual interpretation that depends merely on one’s level of involvement. The meanings attributed to this practice are tied to one’s intention and initial expectations. For those who turn to a mandala-creation practice as an opportunity for creative expression, it is nothing more than a relaxing artistic experience. Regular practitioners, however, attribute a much higher value to this practice because they apply a two-part approach, of which each has a slightly different meaning. Through the creation process of a mandala, these practitioners strive to achieve meditative states free of self-evaluation. Contrarily, the purpose of the translation process is that of self-reflection. Thus, as a whole, this practice becomes a tool for transformation and gains spiritual meaning. It is exactly through an analysis of different forms of creation that art reveals itself in often overseen potentialities – in this case, the possibility of shaping oneself through the creation of a mandala.

Foto: Vineta Liepājniece

[1] Spirituality. Merriam-Webster Dictionary, n. d.

Website: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spirituality

[2] Harari, Y. N. 2017. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, (p. 214). London: Penguin Random House.

[3] Rubenis, J. 2021. Starp Divām Bezgalībām, (p. 129; quote translated from Latvian). Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC.

[4] Blume, N. Exploring the Mandala. Asia Society, n.d.

Website: https://asiasociety.org/exploring-mandala

Hasty, J.; Lewis, D. G.; Snipes, M. M. Anthropology of the Arts. OpenStax, 2022.

Website: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-anthropology/pages/16-1-anthropology-of-the-arts

[5] Bühnemann, G. 2017. Modern Mandala Meditation: Some Observations. Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol. 18, No. 2 (p. 263 – 276);

Mark, J. J. Mandala. World History Encyclopedia, 2020.

Website: https://www.worldhistory.org/mandala/

[6] Smith, S. Art as a Spiritual Practice. TEDx Talks. 2016.

Website: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wbs0UmtNTmk&t=268s

[7] Cybulski, A. The Space Between: Ritual and the Practice of Art, n. d.

Website: https://www.dappledthings.org/deep-down-things/2804/the-space-between-ritual-and-the-practice-of-art

[8] Campbell, L. H. 2005. Spiritual Reflective Practice in Preservice Art Education. Studies in Art Education. Vol. 47, No. 1 (p. 51 – 69). Publisher: National Art Education Association.

[9] Gracia, M. F. 1981. On Mandalas. Current Anthropology. Vol. 22, No. 6 (p. 706). Publisher: The University of Chicago Press.

*Helēna Kārkliņa is a student of anthropology at the University of Latvia and a self-taught visual artist. The article is based on her research "Art as a Spiritual Practice: The Meanings of Modern Mandala-Creation practices,” as part of anthropological studies at LU.