Muteness

Roy Brand

A short essay about the relationship between muteness and violence, and about an opportunity for change that arises out of contemplation

Taoism suggests that non-action (wu wei) is the only reasonable way of relating to evolution.

Not a different action, but non-action. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, The Second Coming

Part One

We cannot fight chaos. Chaos feeds off of the struggle against it, and it is empowered by opposition to it. Instead of fighting, we can ask ourselves: whom or what does chaos serve? Who profits, or can potentially profit, from the vagueness and the distraction which chaos creates? To observe without acting, to experience without externalising – it is in this way that the world will change from within. The only possible revolution is an internal one: from disorder to form, from blindness to insight, from violence to beauty and from chaos to cosmos, a well-tempered universe which is constructed out of mutual relationships and reason.

Beautiful and blue twenty-year-olds. I can feel their sadness as they are locked into their screens. I feel their longing for something different yet lack of ability to imagine anything different. There is no way out. Everything is blocked inside, and the external world appears chaotic yet fixed.

If you have been living in the world of the past twenty years, then you have been living inside of the rabbit hole of “oneself”, a reverberatory space that only repeats what has already been said. This reminds us of the curse of Echo and Narcissus: the former can only repeat what has been said, and the latter is fixated on his own image until death. Life now appears to be quite similar, a repetitive binge of echoing selfie clips. Gradually, the familiar turns uncanny and the day-to-day becomes weird and surreal. Things are familiar to the point of estrangement. I am the walking dead, a digital bot who acts in the destruction field of the twenty-first century.

My fear is that young people today will convert alienation and sadness into anger and that this anger will eventually find expression in hatred. This not to speak of a kind of creative, passionate, poetic, erotic hatred, but of a hatred that is oppressive to passion and of an anger that is impotent. Muteness turns into violence.

We are currently at the extreme end of an unequal distribution of knowledge. There are very few things which I know, yet a lot of information appears to be “out there”. And so, more often than not, out of fear or laziness, I rely on the mediation of experts: commentators, spiritual or religious savants, institutions, political leaders and anonymous corporations. I feel lost in the overload of information. But this is exactly where a revolution is required – an internal revolution wherein I reclaim ownership of the information I consume and disseminate. This entails a change in attitude and a willingness to act without being paralysed by hesitation. The attitude changes from passivity to ability, and the will becomes harnessed to two horses: passion and reason. In other words, we need to reclaim our ability to feel, understand, judge and navigate for ourselves within the overflowing stream of information.

Revolutionary moments in history are different from one another. A revolution can never be repeated. But there’s one theme that can be detected, and it has to do with the relationship between information and knowledge. Information is composed of external data that controls the system and holds the power, while knowledge is the internalisation and the understanding of how power works. The relevant question to every revolution pertains to the adequacy or inadequacy between the amount of information that circulates in the system and the ability of the individuals involved to grasp and use that information. One thing is clear: revolutionary moments occur when information that has up until that point been held by a small segment of the population suddenly becomes accessible and open to all.

The printing revolution in the fifteenth century, the industrial revolution in the eighteenth, the communication revolution in the nineteenth century and the digital revolution in the twentieth – in all of these there was a shift in the way in which information was shared and distributed. When the floodgate was cracked open, information moved out of the hands of the privileged few and into a shared common space. The invention of print made books available to the public, modern industry and machinery resulted in a public that was mobile and centred in cities, and the digital revolution brought the world to our fingertips. But with every new step, new inequalities and injustices appeared.

Now, for example, I know that governing bodies, states and corporations hold an immense amount of information about me, which, for the most, I have given unwillingly but with legal consent. The composition, details and consequences of such information is, however, outside my purview. To better balance this inequality, I can, for example, disconnect myself from “free services”, thereby restoring control over my actions in the shared virtual space. I can also try to better understand the ways in which big data works and navigate my way in a much more intelligent, responsible and critical way. There is no doubt that, in the past couple of decades, technology has developed at a much greater speed than that of consciousness and that technology, rather than human reason and action, is in fact governing society today. My claim is that, in order to make a change, we must first move the control to the participants.

We need to take back possession of our information because information is essential for democracy – consistent, high-quality information from reliable sources. Like air, water and the sky, information belongs to everyone.

The story of the past two decades is the story of surveillance, the constant surveillance done by governments and corporations for profit and control. This surveillance is ruinous and stifling. It manipulates communication and stifles creativity and freedom. The digital space must be democratised while democracy itself needs to grow and evolve to counter new challenges. In the long process of attempting to democratise information and open a shared space, we have first liberated physical locations such as the countryside, the cities and the streets. We (our common ancestors) then liberated institutions, occupations and forms of expression. We have taken possession of palaces and have turned them into museums. We have turned monasteries into libraries and universities. The next step would be to liberate virtual space. This would be a long process (a revolution spread over centuries), but it can start now with a change of consciousness and a new attitude, namely, that virtual space is our own. We need to take back possession of our information because information is essential for democracy – consistent, high-quality information from reliable sources. Like air, water and the sky, information belongs to everyone. Information is our natural habitat.

Shahar Afek. Calicotome villosa, 2020, Ink and watercolor drawing on paper 42x29 cm

Part Two: Muteness and the Art of Reading

Muteness is a characteristic of our time. No one dares to speak out, not in class, not at family dinners, not on paper, not verbally. Muteness penetrates inwards and strangles our thoughts and passions, imagination and creativity. Muteness and violence inward and outward. How few are the people who still possess the art of conversation, who know how to tell a story, to listen and to laugh, to continue their partner’s train of thought and deepen it into an open, shared fabric. A real conversation requires real listening – not someone who tells you who you are or what you “should” do, but a form of open dialogical attention which enables that which cannot be realised individually.

I want to propose the arts, and especially the art of reading, as a cure for muteness.

I want to propose the arts, and especially the art of reading, as a cure for muteness. That might come as a surprise since reading is an art mostly practised alone, by one’s self in a room with a book. And yet, reading is a deep journey beyond oneself. As Marcel Proust, a real virtual voyageur, wrote in his In Search of Lost Time:

The only true voyage, the only bath in the Fountain of Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is; and this we do [with great artists]; with artists like these we do really fly from star to star. (Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, vol. 5, “The Prisoner and The Fugitive”)

Art is a journey in time and space, outside of our bodies and consciousness and into that of others, into different times, different thoughts, different desires, passions and fears. When I read Shakespeare, I can feel what it was like living in sixteenth-century Britain. Visiting the Acropolis of Athens, I understand what it must have been like in ancient Greece. This is not a theoretical kind of knowledge but a visceral experience – I am living it. Likewise, the art that we do today will tell our stories to prosperity. It is like sending a capsule of experiences into the future. Art is our magical Noah’s Ark which will land after the flood on a future Mount Ararat, and whatever we would like to keep of our present can thus be reincarnated. Art is a form of communication – not the communication of this or that bit of information, but the sharing of experiences and forms of life.

Art is our magical Noah’s Ark which will land after the flood on a future Mount Ararat, and whatever we would like to keep of our present can thus be reincarnated.

Proust’s art is, mostly, the art of reading and writing. Part of today’s muteness is a result of the crisis in reading. How many of us still read, carry books to read while travelling on a bus or train, and keep a few books next to our beds? If we still read, and this I know from experience, our attention is deflated. On screens, the eye quickly wanders, not to other worlds but to the next tab, where it loses itself again. Proust must have had in mind an enthusiastic reader such as himself. He imagined a reader who can hold many details in her memory for hundreds of pages, a reader who can go out for a long, world-discovering journey. In contrast to this reader, the reader of today scans the page to “get to the punch line”. Cursorily scanning for information is a new kind of reading and a new kind of thinking. I want to understand something “straight away”, immediately label it, find its place and move on. Of course, there is no time to absorb the constant flood of information, so I fight this chaos by labelling it and saving what I can. Maybe “one day” I will “go back to it”, I tell myself, when I have just a little more “spare time”, although I know that the amount of information which my phone already contains will take a lifetime to access. This desperate attempt to “save” information reminds me of Walter Benjamin’s story about the angel of history from his last surviving text, “On the Concept of History”.

Paul Klee. Angelus Novus. 1920

Benjamin describes Paul Klee’s little drawing wherein he observes a flimsy angel, his face directed to the past, where waves of ruins pile up. He wants to suspend, awaken the dead and stitch the ruins back together, but the storm blowing from heaven has caught in his wings and is too strong. It pushes the angel backwards into the future. “[W]hat we call progress,” writes Benjamin, “is this storm.” Like the angel of history, we are caught up in this storm, moving ahead faster than we can absorb, experience and understand.

That which is lost during the chase after “the bottom line” is a process of creating deep networks of relationships. This process includes connecting old and new fields of knowledge, discovering analogies between different ideas and experiences, drawing conclusions, examining possibilities, evaluating truths, and also transitioning to other ways of looking and forms of knowing. In the midst of the storm that befalls us, there is no more room for play or imagination. Instead, we experience a downgrading of our levels of empathy and the quality of our awareness.

Here, reading works as a healing force to counteract the storm of information. The intimate and solitary experience of reading, which takes me away from myself and into the realm of deep empathy and conversation with the experiences of others, is a curing silence. Silence then, yes, as the opposite of muteness: quiet meditation and reflection, rather than deafening anxiety and inattention.

Shahar Afek. Petrichor, 2020, Ink and watercolor drawing on paper,30x20 cm

Part Three: The End

We are on the edge – on the threshold or the cusp – of a transition period. Something is closing behind us while something is yet to come. We are stepping towards the end of the world, at least as we know or imagine it to be.

How can we understand this sense of an end without a new beginning? The future or the belief in a future, which was so vital to modernism in the twentieth century, is dissipating. Do we still believe in the future, in the future of modernity? Do we believe in progress? Or do we yearn for some radical break, some inexplicable messianic transformation? In the nineteenth century, Nietzsche spoke about the death of God. “Haven’t you heard,” the madman asks in The Gay Science, “about the death of God?” As if the death had already happened but the horror had not yet sunk in. We killed him when we stopped believing: “I am telling you; we have killed God – you and I! We are all murderers. But how did we do it?... What have we done when we have untied the earth from its connection to the sun? Where will it go now? Where will we all go now?” (The Gay Science, section 125).

Each and every one of us has their own utopia, and in it we or our descendants can achieve happiness and possibly immortality.

Even though the remains are still among us and the corpse not yet utterly cold, there is no doubt that faith in God and the frightful system which it entailed have withered. But what has come to replace it? Nietzsche argues that we cannot really live without faith, and so we moderns come to replace God with a secularised belief in progress. But what is progress? Simply put, it is the belief that “things will be better” in the future. Better how? This is undefined, and this is also the beauty of the whole concept, because it gives us the opportunity to shape the future like a fantasy. Each and every one of us has their own utopia, and in it we or our descendants can achieve happiness and possibly immortality. Many today are waiting for technology to save us from the hell which we have created and lead us into the promised land of artificial intelligence. This belief – that someone or something will navigate our lives and save us from ourselves – is still with us today and is still very strong. How can we imagine life without it?

Perhaps the future is our greatest danger? If the belief in the future were to fade, we could then take care of this world and this life instead of the one to come.

Finally, I want to suggest that this belief be cracked open so that we can say, just like the madman, “Have you not heard that the future is dead?” Because it has already happened, although the horror has not yet sunk in. And maybe, just like with Nietzsche and God, the death of the future is not necessarily bad? Perhaps this faith in the future kept us from living as we should here and now? Perhaps the future is our greatest danger? If the belief in the future were to fade, we could then take care of this world and this life instead of the one to come. In the present to come we could do things for their own sake rather than instrumentally as means to other ends. My writing here would be only for you, and your art would be only for us; we would not accumulate assets as if we were to live forever, and we would not burn the club on the way to glory. We would have to learn how to live, as the poet writes, “without future, hope or dream”. What would the world look like without a future? Not so different from the world as it is now, except, perhaps, without the deceiving disguise of “soon, later would be better”. The end of the world is not tomorrow; it is already here.

Translated from Hebrew to English by Anna Sharon

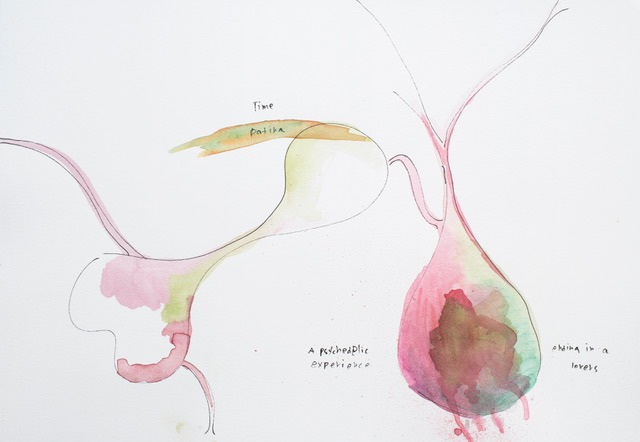

Title image: Shahar Afek. A psychedelic experience that ends with lovers, 2020, Ink and watercolor on paper, 30x42 cm

Shahar Afek’s drawing is part of the “Inner Space”, the inaugural exhibition of Parterre, a new project space for art and philosophy in Tel Aviv