We own our unconscious processes

Una Meistere

An interview with social psychologist John Bargh, Professor of Psychology at Yale University

John Bargh is a social and cognitive psychologist and professor at Yale University, where he has formed the Automaticity in Cognition, Motivation, and Evaluation (ACME) Laboratory, dedicated to studying automaticity and unconscious processing as a way to better understand social behaviour and free will.

Over the forty years of his career, he has been studying the unconscious mind, trying to understand how much of what we say, feel, and do is under conscious control. And, more importantly, how much is not. Including seemingly mundane episodes, such as how the physical sensation of warmth (even if only in the form of a cup of tea) and its opposite, the sensation of cold, affect our social behaviour. Or how our basic genetic needs – to survive, to be physically safe and to avoid disease – encoded eons ago in our evolutionary past, can be linked to our present-day political views and attitudes towards migrants.

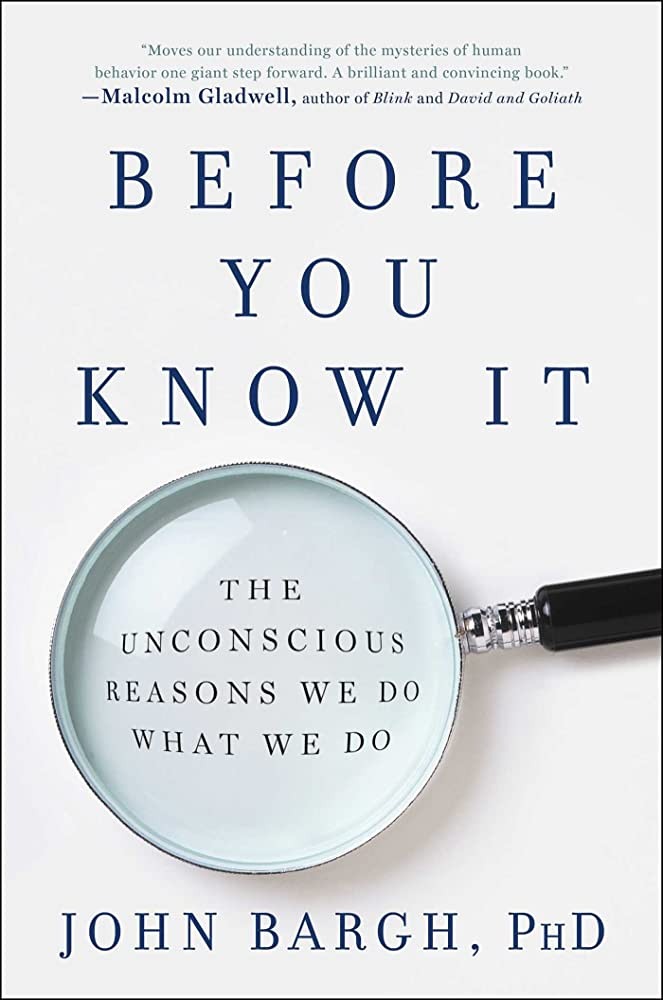

John Bargh has authored more than 240 peer-reviewed articles, written chapters in over 30 books, and in 2017 published his book Before You Know It: The Unconscious Reasons We Do What We Do. Starting off with a quote by Albert Einstein: “The distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion,” the book is brilliantly written 40 years of insight into the world beneath the surface of our consciousness – one where the past, the here and now, and the future are equally present. A world where our conscious and unconscious mental processes operate in tandem to form an indivisible whole – our mind. By understanding, being aware of, and taking responsibility for these processes, we are able to steer the ship that is each of our lives more skillfully and knowledgeably – or, in Bargh’s own words, the purpose of the book is “to put you inside the DJ booth of your mind so that you hear better what is really going on and can start controlling the music yourself.”

In person, John Bargh is smiling and full of good humour. Yet, with a realistic and healthy observer’s point of view, he is very well aware of the pessimism linked to our evolutionary instincts and which, for the most part, explain why, despite all good intentions, humans still find it so difficult to listen to others, to be open, to promote equality, and to ensure peace on this planet. If we want to move forward – towards a better version of ourselves and of society as a whole – we need to expand our idea of who is the "I". We are all connected; it’s part of our evolutionary past and "not just through our visible actions, but through our invisible thoughts as well." We have learned a lot, but there’s still a lot we do not know. That is why it is all the more important for us to keep an open mind, and that is what the following conversation was all about.

I’ve read your book twice, and I really like it. It’s kind of like a “user’s manual” for the times we’re living in. We all know that the world is changing very fast, and we’re trying to adapt to these changes, yet in the meantime, everything is uncertain. One of the most important things that can help us navigate this uncertainty is creativity – finding creative solutions and/or new ideas for almost every field of life. In your opinion, what is this strange thing that we call an “idea”? And where do they come from? How can we effectively tune into them? Sometimes, for instance, you’re taking a walk in the forest and, suddenly, out of the blue, you sense the fragile glimmerings of a great idea; whereas at other times, you can sit for hours in front of a blank page and can’t come up with anything good if your life depended on it.

That’s a wonderful question. I’m actually working on a second book right now on the stream of consciousness – what’s in the mind and why it’s there, what are the sources of your thoughts and ideas, and how it’s all mixed together. It’s basically the extended present, a concept that philosophers like William James and Henri Bergson talked about a long time ago.

One important thing you mentioned in your question is the fact that ideas are fragile. When we have an idea and insight, some kind of creative breakthrough, we have to treat it like it’s almost a special painted Easter egg. It’s a delicate work of art that’s so fragile that we must share and protect it. And how do we do that? We don’t take it lightly. A lot of times people just think, Oh, I came up with an idea, it’s in my memory now and I’ll never forget it. Well, five minutes later you’ve forgotten it, and you wish you’d done something like writing it down.

When we have an idea and insight, some kind of creative breakthrough, we have to treat it like it’s almost a special painted Easter egg. It’s a delicate work of art that’s so fragile that we must share and protect it.

So, I have all these techniques that I do when I come up with an idea. And I’m always coming up with an idea – we all do, right? Like in the shower, or when I’m out for a run or a walk. Exactly when I don’t have the ability to write it down. So I always carry my phone with me, and on the iPhone, I tell Siri to send myself an email. So I send a dictated message to myself, and, of course, Siri makes hilarious mistakes in transcribing what I’m saying, which are funny to read, but at least I preserve the idea. I don’t take it lightly. There’s now this programme called Otter which, when you have, for example, a Zoom conversation, it transcribes it. And more than once, we were talking and someone interrupted, and I thought, What was I talking about, like, two minutes ago? There was this idea... But with Otter you can go back and find it in the transcript. These kinds of aids for preserving the fragility of our conscious contents are really helpful. I mean, you really have to make use of them.

But there’s two things here. The idea comes from a constellation of circumstances, which is hard to replicate. So many things are causing you to have that particular idea in that particular moment. Psychology is not simple — it’s complex, there’s so many things. Your physiological state with coffee, the fact that you’ve recently thought about something on recent experience, the fact that you have a problem you’re trying to solve. All these things were active at the same time, and to think that you’re going to easily recreate all those things in the future is a mistake. So, number one, write it down. Number two, preserve it, because don’t count on it being there when you come back to it.

The second part that we’re talking about is those times when you and I have a conversation, and you suddenly have an idea and you interrupt me because it’s really important. This is tricky. You’re interrupting what I’m saying; I may lose my train of thought because you interrupted. At the same time, you interrupted because if you don’t interrupt and say it, then you’ll forget it. So now, with two people being creative together, it’s a very delicate little dance where you have to respect the other’s interruptions, but you also have to respect that by interrupting, there’s a potential cost. I know that the people with whom I have three-, four- or five-hour conversations — we would just go on forever if we didn’t finally get hungry or have to run to the bathroom or something, right? When we do that, we have an atmosphere of trust; we have an atmosphere in which we both have the same goal, we’re both working on the same problem, the same issue. So we both want to get there to find an answer. So we allow each other the interruptions because we know that won’t be abused, that I will only interrupt you if it’s really important, and I know there’s a potential cost. So this is where when you have a collaborator or friend or somebody you work with that you’ve developed a relationship with and you can be creative together — that is so special because you have to trust each other (which is not always there), and you have to have the same goals (which is not always true). You have to develop respect for the other person and not dominate, as in, my ideas are better than your ideas – You be quiet, listen to me, I am so important. You have to be equal. It’s not easy to achieve all these different things. But once you have that collaborative relationship, that leads to the last part of my answer.

Francis Crick and James Watson were the people who discovered the DNA molecule – the double helix structure. Ten years ago, Watson wrote about that discovery in the 1950s; he said that at the time, that was the Holy Grail – everyone in biology and genetics was trying to discover the structure, but they couldn’t figure it out. He said there were many people working on this, and he admits that most of these people were smarter than [he and Crick] were. There was one person in particular, the biologist Rosalind Franklin, whom Watson said was the genius. And she knew she was so much smarter about this than anybody else, but she worked alone. Watson said, and I’m paraphrasing, What Crick and I had to our great advantage was that we worked together; we collaborated, and two minds have always got to be better than one. And the dialogue that you create between two people starts to mimic the dialogue you have with yourself when you’re consciously thinking. It’s even better because it’s like a Hegelian dialectic. That’s what Hannah Arendt said in her beautiful book The Life of the Mind — that’s what our conscious thought is – it’s a dialectic between me and myself.

The problem is when you are doing the dialectic to yourself – when you’re on one side of it, you might forget the other side of it. And then you can’t hold both in memory; it’s really hard to do that in your own head. But with two people, you can have the dialectic. And when you finish your say, the other person can have their say, and you can just listen and rest. When you’re doing your own thinking, you can’t rest. It’s hard to sustain it. When you have a collaborator, not only will they often add new information and new ideas that you probably couldn’t have yourself, but it also allows you to rest and listen. And then when they’re done, you go. And that’s so much better. In fact, there’s people who say that our consciousness itself came out of communication with others — that by hearing ourselves speaking through our own ears, we realised what we were saying and internalised it.

In fact, there’s people who say that our consciousness itself came out of communication with others — that by hearing ourselves speaking through our own ears, we realised what we were saying and internalised it.

I can go on about this forever because I’m writing a book about it, and I’ve been thinking about nothing else for a couple of years. Little children develop the capacity for conscious thought around age two and a half or three. The person who discovered this, almost 100 years ago, was the famous Russian child psychologist Lev Vygotsky. He noticed that when children are developing self control, they talk to themselves out loud. And I saw this with my daughter when she was three years old – she would say to herself: Now I’m going to the bathroom. Now I must get this paper. Now I must show my daddy my art. She would say these things as she was walking around the house. She was not talking to me. She was talking to herself. She was giving herself commands, in a way. And over a period of a month or two, they internalise and become conscious thought.

A lot of people have said that our conscious thought really is an internal simulation of our more natural communication with others. What this all boils down to is – the best way to have ideas is to have somebody to talk to who shares your goal of finding the answer to a problem, and collaborate with them. In my 40 years in this field, my cherished memories of what was the most fun was when I had a collaborator that I just talked to all day, and we worked on and on. I’ve had two or three [collaborators] in my life, and they were the best because it was a flow experience. There were ideas, it was going back and forth, and it was so much easier and fun to come up with answers and solve problems than trying to do it just by myself.

In talking with my artist friends, we’ve noticed that very often, the same idea comes out in two different parts of the world at the same time. These idea-generators are not acquainted with one another, and sometimes have not even known of each other’s existence, so it’s impossible to speak about copying. It’s a kind of tapping into the flow of ideas...

There’s the zeitgeist. For example, when rock music started in the 1960s and 70s, there was this incredible couple of years, a very short period of time. I remember it very well — I was a teenager. I was actually a disc jockey at radio stations for ten years when all this was happening. If you look at what happened in 1971, that one year, it’s like, Oh my god. I’m sure the same thing happened in 1805 with Mozart and Beethoven... There are just times when incredible creative ferment is happening. And often in the same location, like Vienna or New York or London. And then it doesn’t happen. 50 years go by, and nothing else has really happened except that everything’s a footnote to 1971. Everyone’s feeding off each other, everyone’s inspired by each other, and the fact that everyone is so into it means that it motivates you to be into it yourself. I mean, these are usually the early stages of something. And there’s something about fun, excitement and discovery, you know – when everyone’s doing it, and you’re just breathlessly following a track. It’s mainly younger people doing their best work in their 20s and early 30s. And then, like with people, you’re done; it’s not so exciting and new anymore, and now other people are coming in.

It’s because we’re doing it together. It’s because we’re listening and following and being inspired by other people. The fact that these discoveries are happening around the world in different places today, I wouldn’t be surprised at all because of global communication, satellites and internet and everything else. I think that would have been more remarkable 100 or 200 years ago. In fact, Carl Jung, when he broke from Freud, had this idea of cosmic or collective unconscious. And unlike Freud, who insisted that his theory should be dogmatic, and you should just accept it without any evidence, without testing it, Jung said: To hell with that, I’m going to actually do science. I’m going to test my ideas. What did Jung do in 1918 till 1920? He went down the Nile River, to the source of the Nile, to look what kind of symbols people who are detached from the rest of the world use. He went to Native American reservations in New Mexico and Arizona, to the Hopi Indians. And this was before highways, before cars, even; it was not easy to go to the Native American reservations in the desert. He went around the world, to very inaccessible places, and collected his evidence on symbols. He saw that the symbols being used by the Hopi in Arizona are the same as those being used by people who live around Lake Victoria and the source of the Nile in Africa – and they couldn’t possibly have communicated with each other back then. That was where he thought that there was some kind of collective consciousness. Of course, now we pretty much realise what caused this – that there is a human nature that evolved, that we come from shared ancestors, and that there is something about the primitive human mind which generates these symbols everywhere. So, the fact that today it happens in one place and then somewhere else around the world is probably related to the internet and communication, but also to the fact that we all have the same primitive yet evolved brain pretty much intact. All of us share that, and that’s where these ideas come from. Because everything that’s in your consciousness has to logically come from your unconscious. It can’t come from anywhere else – unless you believe in divine inspiration and that you’re somehow not human – it has to come from our unconscious processes. And because of our shared evolutionary past, we share most of those mechanisms.

In your book, you talk a lot about the fact that we are not as firmly in control of our thoughts and actions as our consciousness leads us to believe. This is hard to accept. We are living in the 21st century now, but our minds are still following those patterns that were set back in the Stone Age. And I think that the war taking place here in Europe is clearly telling us that this really holds true. We may think that we know why we are doing something, but there’s often a deeper underlying reason. Is there any way we could reprogram ourselves, since we now know more about how the human mind works, or is this not possible?

You’re not going to like my answer; I don’t think anyone would like this answer. There was a great Viennese philosopher of science named Karl Popper. Actually, Popper is the one who really didn’t like Freudian methods, and he criticised all science because science, he thought, was confirmatory and it wasn’t testing hypotheses. There was no way to falsify theories because you just looked for evidence in favour of your theory. So, in 1934 he wrote this beautiful book in German, The Logic of Scientific Discovery. It was published in English in 1952, and it’s the standard work on experimental method and logic – how you can really use scientific method experimentation to learn.

Popper also wrote something else. During WWII he left Vienna and lived in exile in New Zealand as a refugee from the war. The title of the book he wrote there is The Open Society and its Enemies, and it was published close to the end of WWII. Then he went to England and became a professor at the London School of Economics, I think. Basically, Popper attacks Plato right off the beginning because he thought Plato was a totalitarian-dictator type who preached conservative principles. But then he went on to argue, very persuasively, that we’ve been in tribes for most of human history, and all tribes have a leader. And it’s so easy for demagogues to cause us to go right back into the tribal mentality because this is how our minds evolved for millions and millions of years. Democracy is so recent. And it’s such a fragile and such an unnatural thing for humans who evolved in this tribal sense. It’s so easy to get rid of a democracy with demagoguery, and with an appeal to the tribal “us versus them”. And of course, that’s what’s happening. And it’s happened here, obviously, in the United States, especially since 2016. And now it’s very much a “divide and conquer”, an “us versus them”. We have tribes and we don’t listen to each other. The internet made it worse; social media has made it worse. We only listen to our own “bubbles” – to people who we agree with and not to people we don’t agree with. And unfortunately, it’s all amplified and played into our evolutionary past, which is tribal. So if you ask, What can we do about this?, it’s going to be really hard to come up with any kind of an answer because you’ve got a basic human brain designed for survival. And the way we survived was to join up in tribes and groups to fight off the threats to us, i.e., the other tribes and groups.

It’s so easy for demagogues to cause us to go right back into the tribal mentality because this is how our minds evolved for millions and millions of years. Democracy is so recent. And it’s such a fragile and such an unnatural thing for humans who evolved in this tribal sense.

In his book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2011), Steven Pinker (who’s written many great books) pointed out that throughout human evolutionary time, until very recently, one out of four males died because they were murdered. In fact, when you look at ancient human bones, actual violence and damage is visible. One out of four males were murdered by another male. Back in the year 1100 or so, it was one out of 1000, and now it’s one out of every 100,000. So we are getting safer, in a sense, but our evolutionary history is to be worried and very wary of other people, and the way we solve that is to join together in groups. That was the solution in the past, up until 2000 years ago. For people living today in isolation from the rest of the world, for example, on remote islands in the Pacific, the ratio of of males being killed is still one out of three or one out of four.

So there’s something we’re doing as a society to make things safer, but it doesn’t change human nature, and it doesn’t change what’s inside of us. People in general are just so easily swayed by appeals to groups, to “us versus them”, and to not listen to each other because that’s how we survived. It’s ingrained in us as far as a survival and safety thing, which is our primary motivation.

So, I’m really pessimistic. You can see this with demagogues… it’s just too easy for them. We follow a strong leader, we don’t resist, we snap into line. It’s something we had to do to survive in the past. In the Middle Ages, when strange people showed up at the village gates, that usually wasn’t good news. We sort of had to say, Okay, you’re our new lords and masters, we’ll do what you say and then we’ll be fine. We had to do that to survive and have kids and have a life. I read Popper, and I’m like, my God, it’s so sad because democracy and equality and fairness and all these wonderful things that we’ve shown are possible – they’re human ideals! Why do we so easily disrespect them and get rid of them when they’re really our crowning achievement?

What is the effect of fear on social change? Of all our basic emotions, fear is the one that is manipulated most successfully. As you mention in your book, when you use fear as a weapon, you can easily turn liberal people into a conservative crowd. We’re seeing this happen in many places now.

Well, I got kicked off from Facebook and Twitter for saying that. I’m permanently suspended from both. What I did wrong was I reposted on Facebook and also on Twitter my Washington Post editorial – I wrote exactly on that subject, about how safety is so primary, and what people lose in that. And I got attacked. People said – you’re saying that conservatives are scaredy-cats, and we’re all afraid and this kind of thing. And what they missed was that this works both ways. There was 20 years of research before our study that showed that you can threaten liberals and make them conservative. All we did was actually change conservatives into liberals temporarily – by making them imagine that they are completely safe. In America, we had the famous President Franklin Roosevelt who said, We have nothing to fear but fear itself. He was liberal; he was trying to make people feel safe. Barack Obama said the same thing in his last State of the Union Address in 2016. Sorry, I’m talking about the United States so much, but it is the most powerful country in the world and with the best military and we’re so safe – so why do we act so afraid? Why do we act so scared all the time? You know, we shouldn’t be.

There was 20 years of research before our study that showed that you can threaten liberals and make them conservative. All we did was actually change conservatives into liberals temporarily – by making them imagine that they are completely safe.

So, liberals are trying to make us feel safer. And conservatives are trying to make us feel afraid because they want power, they want votes, and unfortunately, these are really powerful mechanisms that go both ways. But it’s much easier to get a person to be afraid than to feel safe, because of the cost of being wrong. If you are safe, and you let your guard down, the cost is much higher than being afraid and not being right about the threat, because at least in your worst case scenario, you’re ready for it. So it’s much easier to do the fear than it is to do the safety. We managed to do it in a really nice way, but I don’t think that many people in the world today feel all that safe.

Historically, in the history of the human race, I don’t think that we’ve had many times where we felt all that safe. It’s a wonderful feeling, but it’s ephemeral. It’s fleeting. So yeah, we are manipulated all the time. And that’s what I was trying to say in my book. If you’re reading my book, you’re not the only people who know this; the people who know this don’t want you to know this because these are the levers that are used by advertisers or politicians or whoever. I’ve known this from knowing people in business and advertising and marketing. They’ve known this stuff since at least the year 2000, and they’ve been using it in advertising to get you to buy their products. And I’ve gotten some heated words from people in consumer product companies, because I’m basically telling people how it works. And we’re not supposed to do that – according to them. My problem with writing books on unconscious influences is it’s a really hard sell. Because you tend to just look to your own experience, and you say, I can’t remember a time that’s ever happened to me. And so people dismiss it as it can’t possibly be real. And that plays right into the hands of people who are using these kinds of techniques and levers.

It’s really interesting that we can so easily fall into the trap of fear; meanwhile, we have to work very hard to be joyful. And if we look at basic human emotions, the positively charged ones, like joy and happiness, are in the minority; the rest are fear, anger, sadness, and surprise.

And anxiety, which is, of course, related to fear but is not the same as fear. Anxiety and sadness and all those bad things are, I’m sure, the most common emotions that we all feel, and it’s too bad. You know, someone from evolutionary biology once said something on the order of, We did not evolve to feel happy. Being happy was not selected for by natural selection. What was selected for was survival and reproduction. And if being anxious helps you survive and keeps you safe (compared to not being anxious), and then helps you live long enough to have babies, which is what your genes want, that’s what will happen. I mean, I’ve seen horrible, tragic, incredibly sad movies about penguins, for example. One is called March of the Penguins, and it’s the saddest thing because these poor penguins are trapped in an ecological niche where they basically have to live in horrible conditions and try to keep their eggs warm as a group. Of course, it’s very hard for them, and often times the egg freezes and cracks and their baby doesn’t survive. They’re trapped in the cycle because that’s the cycle of making more penguins. But it’s hell, and that’s what they have to do because you’re in that cycle. Evolution just does not have a reason for making people happy and joyful. Unfortunately. So we have to overcome that and transcend it.

Evolution just does not have a reason for making people happy and joyful. Unfortunately. So we have to overcome that and transcend it.

Maybe we can try to transcend it by making joy and happiness habits, as implementation intention, which you suggest in your book.

Well, that’s the other message of the book, basically – once you know how these things work, this is your user manual, right? And this is how your mind works. You didn’t know about all this but now you do, and you can use it to your advantage.

You know, one of my heroes is Naomi Osaka. She’s a tennis player, and she was the one who publicly said: I’m not going to go to press conferences anymore. Why? Because they make me feel miserable. They attack me. They make me feel depressed. They make me feel worthless. Here I am devoting so much of my time and even my winnings to charity and trying to do good in the world and I get attacked with, “Oh, you’re just doing this for publicity, for your brand to improve,” and this kind of snide stuff. I leave these press conferences feeling depressed and not wanting to even continue. And so she said, You know what, dammit, I’m just not going to go to these press conferences anymore. And you can fine me and you can ban me from tennis tournaments, you can do what you want. But for my own mental health, I choose not to enter these situations anymore. I was like, thank God, someone is starting to do this kind of thing. Because of the kind of stuff that we are supposed to put up with in our life. For me, I would say it’s faculty meetings, meetings with colleagues who look down their noses and think they’re superior. I’m sure every aspect of life has this; I’m sure businesses have this, I’m sure any organisation has it – we all have this, right? And Naomi just stood up and said, I’m going to choose not to enter these situations, because these situations make me feel so bad. And I said, yeah, we can do that, we can just not go into situations where we know it has this damaging horrible effect on our mood and our self-worth for the next three, four days.

I try to implement that in my own life, too. We have this choice. But we think that we have to do these things, and we don’t realise that we do have the agency and the ability to choose our situations. We can construct our environments in our world to make us feel better and happier. We don’t have to buy the stuff that we don’t want to eat in the middle of the night because we’re on a diet. We just don’t buy it in the first place – we make our environments to attain our goals, we construct them that way. And those are the people who are successful and happy. They set up their worlds to make good habits of the things they want to do, so they don’t have to think about it. They don’t think to themselves, Oh, I must do my exercise, or I must do my diet, or I must do this or that – they set it up as a habit. And once they do that, they don’t have to worry about it any more; they just do it. And those are the people who turn out to be the ones who get their goals accomplished and are happier than the rest of us.

It’s funny, because the old research on motivation and how people get what they want is all about willpower – Oh, I am trying so hard... Now that’s exhausting, and it doesn’t really work overall – you lose track and forget what you’re trying to do. The conscious approach to this is problematic. And so setting up your world to have it done for you easily, through implementation intentions or through habits especially, makes your life so much better. I’ve used that. I’ve noticed things that make me really unhappy when I say things to my little girl, or when I treat her in a certain way, and I feel so bad afterwards. I don’t want to feel that way; I don’t want to do that to her; I don’t want that to be our relationship. So do something about it. And you can – the implementation intention is the road to good habits. It’s not a solution by itself, but it’s the way to break the bad and start creating the good habits. It’s the bridge between where you are now and where you want to be. And all it is, is using an unconscious mechanism. It’s basically delegating control over your own actions to a reliable event outside of you. When I step out of the car onto my driveway, I will immediately forget about work and I’ll immediately look at my house and say I’m so happy to be home. And I’m going to really enjoy playing with my little girl and hugging her, and all that kind of good stuff, and I’m not going to bring my work life home with me. And then I step out of the car and I realise I’m home, and it happens. It’s like magic. But it’s not really magic because we know how it works. But it’s magic in the sense that you didn’t have to try at the time to remember to do it. It wasn’t your conscious mind doing it, but it’s a big part of your mind that operates unconsciously, that’s still you, and it’s doing what it can to help you.

The implementation intention is the road to good habits. It’s not a solution by itself, but it’s the way to break the bad and start creating the good habits. It’s the bridge between where you are now and where you want to be.

You mentioned hugging. I think we all know how emotionally important this is for all of us – to hug your kid, your parents, your friends. It was one of the things which became nearly impossible during the pandemic, and it’s possibly played a part in the ongoing mental health pandemic we are experiencing now, especially among young people.

The thing about hugs is that they’re so important, and especially for the first year or two of infancy. Because it’s like a primitive signal. Newborns are ignorant – not in the figurative sense but in the literal sense. I mean, they don’t know anything; they may be brilliant geniuses, but they still don’t know anything. And what they respond to are the evolutionary things, like feeling a person’s body warmth, being held close – it’s a primitive signal that you can trust this person.

Now, we also know that this feeling of bonding with the caretaker – with the mother or the father, plays out for the rest of your life. If you feel attached and bonded with your mother and/or your father when you’re one year of age, then you’ll have all these better outcomes with your relationships for the rest of your life, as in, friends in school, and not so many divorces or breakups in your 20s and 30s.

But then, during the pandemic, we couldn’t touch each other as we used to; we couldn’t hug our friends and relatives. I don’t want to get into it because it’s so heartbreakingly sad about the people who were dying of COVID and couldn’t have any family members near them and couldn’t have anybody even touching them or holding them because it was this horrible, contagious thing. You know, one of the more poignant inventions was that the personell in the hospitals started filling up surgical gloves with hot water, so that patients would have a warm “hand” to hold to make them feel better. Essentially, the substitution of social warmth with physical warmth.

It’s a horrible feeling to be isolated, it’s a horrible feeling to be lonely, to be homesick…it’s one of the worst feelings. Because we actually have to be with each other. And we’re finding out now that even when we’re not, we find ways – we have reality television shows where we know this group of people, and we’re so eager to watch it. We don’t really know them, they’re only on television, but it helps satisfy this feeling of having friends, knowing people, and we can follow their lives. We search out ways to satisfy that need in so many other ways besides actually being with a person. Like reading stories where we know the characters and the protagonist, and following them through the narrative. And I do this myself; for me, the best things I’ve read are series in which the same people go through their life — they get older, they have kids, and you follow these people through book after book. It’s like a substitute kind of relationship with people that you sort of know or feel you know. We look for these relationships everywhere, and they really are a big part of how we use our leisure time. It is such a basic, important need.

In your book, you write a lot about cold and warmth, and how the sensations of cold and warmth affect our emotions and social interactions. You reference Dante’s The Divine Comedy: “[…] what Dante could not have known – but somehow did, without the benefit of modern science – is that seven hundred years later, neuroscience would show that when a person is dealing with social coldness (like betrayal of trust), the same neural brain structures are engaged as when that person touches something cold, or feels cold all over.” And a similar tendency can be drawn with warmth. How much do these “warm” and “cold” experiences affect us in daily life, and how are they connected with our evolutionary past?

You know, what’s funny is that in my field, there’s such resistance to this idea that the body and the mind are connected. I mean, it’s unbelievable. The people who [study] cognitive psychology are more aligned with computers and artificial intelligence, and they sort of see the mind as an abstracted, separate thing from the rest of the body. And I just don’t understand this. It goes back to Cartesian Dualism, the separation of the mind and the body. They really resist the idea that there are physical sensation influences on how you feel, and on your mind.

You know, we’ve had 10 or 15 years of being laughed at by our own field because we think that these things happen – despite all the evidence. So, unfortunately, I’ve had to live in that world where no one really believes what we say and find – but there’s so much evidence on this now. And people are actually putting this into practice. The heat and warmth treatments are actually being effective now with hospitalised severely depressed people. A daily heat treatment of 15 minutes over two or three weeks can cut their symptomology in half, i.e., the bad feelings and bad symptoms they are having. And these are hospitalised depressed people, so they’re really depressed and not just sad. This treatment really is effective.

The people who work on brain chemistry and physiology have already identified that there’s a circuit from feeling warmth on your skin – there actually are brain pathways that respond to this. Warmth on the skin opens up the same pathways that have an effect on brain chemicals that make us feel happy. It opens up the same pathways that antidepressant medications open up – the warmth effect actually has the same effect on the brain as an antidepressant medication. That’s how powerful this is. And they’re really detailing exactly how this happens through all the different circuits of the mind and of the brain.

There’s so much evidence on warmth and social warmth. People keep diaries of how hot they felt during the day and all the things they did, and the people who felt warmer actually did more pro-social things for other people that day. In terms of brain-imaging work, it’s the same little area of the brain, the insula, that becomes active both with physical and with social warmth. So it’s human nature. It’s connected physically in the brain that when you feel physical warmth, you actually feel more socially warm. It’s not the only influence on us, but we’re wired for this effect because we are born as totally helpless infants that have to trust the people around us, and we trust the ones who feed us. We trusted the ones who were holding us, keeping us warm. Back in the day, being warm was not a guaranteed thing. We didn’t have houses and central heating and all this wonderful stuff. We huddled together and kept warm, and if we didn’t keep warm, we died. Staying within a narrow range of body temperature, i.e., staying warm, was just like needing food, feeling thirst, and everything else critical for survival. No wonder it’s wired in. That’s how natural selection works. But it actually is an amazingly important connection between our physical sensations and our mind, and our social relations and our mental health as well.

Warmth on the skin opens up the same pathways that have an effect on brain chemicals that make us feel happy. It opens up the same pathways that antidepressant medications open up – the warmth effect actually has the same effect on the brain as an antidepressant medication. That’s how powerful this is.

Speaking about resistance, at the moment one such issue is how closed the current field of psychotherapy is to integrating new tools, like psychedelic therapy, for instance. Despite many ongoing and already completed clinical trails proving their effectiveness, there appears to still be strong resistance to such new tools and methods.

And in the meantime, people are suffering. This is what I really hate about our own mental health operation, and the people who run it in the government. It’s all pills, and it’s all supposed to be pills, and that’s all. The only thing you see on American television commercials are pharmaceutical ads for all the different pills for all the different things because they have so much money, and it’s just dominated by pills.

And if you’re supposed to get therapy, well, there’s no mental health care readily available. Most insurance doesn’t cover therapy. I think the statistics show that 50% of people who need therapy or some kind of treatment are not getting it. 50%! So, here we show something that might help people, the “warmth” idea or things like that, and it’s very easy to implement. But it’s ridiculed – Oh, you think you’re going to cure depression by having people hold a cup of warm coffee? Well, yeah, you can make fun of it, and no, it’s not the only solution, but if it can help – and it is helping clinically depressed people – why don’t we tell people about it more? Why are we making fun of it? Why are we not telling everybody that this is something that might help you feel better? Aren’t we in the business of trying to help people feel better? But no, it’s almost like, Haha, no, no! It’s got to be some pill... And who cares that 50% of these people are suffering and we’re not helping them at all. I’m sure you have the same kind of experiences. It’s just – why are you in this field if you’re not trying to help other people?

I think it is also a fear of stepping outside of the box.

I’ve been outside the box since I started in 1981, and I’ve experienced this my whole career. I’ve always experienced resistance to the idea that there are things going on that we’re not aware of, then resistance to things about how your physical sensations influence your mind. Every step of the way, it’s always been this resistance and ridicule, and everything else. I guess I got used to it…that’s sort of the way it is. But other people don’t have that, and I really worry about younger people going into the field because they know that if they don’t march in line and toe to this assumption, that they’ll be ridiculed and they’ll be attacked on social media – and it’s no fun to be attacked on social media. Anyone who’s gone through it, who’s been a fish in the barrel, you know, will tell you that they don’t realise what it’s like for people until it happens to them. And then they really understand what it’s like. It’s not something you want to go through. It’s sad because it gets in the way of science. Science is no longer discovery and objectivity – it’s like a certain ideology or certain basic belief that you have to subscribe to in order to succeed. And that’s very sad. I don’t know if all sciences are like this. Probably not. But psychology definitely has been this way for a while.

Science is no longer discovery and objectivity – it’s like a certain ideology or certain basic belief that you have to subscribe to in order to succeed. And that’s very sad. I don’t know if all sciences are like this. Probably not. But psychology definitely has been this way for a while.

Nowadays we speak a lot about being “in the here and now” and techniques for mastering it, including meditation and mindfulness. Yet in your book, you say that our mind simultaneously exists in all three time zones at once – in the past, the present, and the future. You also speak about “the hidden present” that affects nearly everything we do. What is the hidden present, and how does it work?

You know, the general writers who really understood people and the mind – like William James, George Miller and Henri Bergson – they talked about the continuity of experience, the stream of thought. There aren’t discrete events, as in, we have sensations and we translate them one at a time – experience is continuous. And it blends and it feels like a stream; it feels like it’s continuing and not breaking up into discrete events. What’s just happened has to still sort of be around and active in your mind to blend in and help interpret what’s happening now – it doesn’t just go away. Especially situational influences, and the context, and all that – it has to continually be active. For example, we’ve been having this conversation; I didn’t have to remind myself that’s what we’re doing over and over again – it’s there in the background for like an hour now. It’s the past merging with the present as the present interprets in terms of the past. But we’re also living in the future because we have to sort of be ready for it. We have to anticipate and be ready for whatever might happen.

I use in my book the example of when people are on commuter trains going from here to New York City: everyone wants to sit facing forward. If you go into a crowded New York City commuter train and you find an empty seat, it’s almost always facing backwards. Those are the least preferable seats – no one wants to sit backwards; we all want to sit forward. And so we’re going through our lives, we’re going through time as things are coming at us and we’re seeing what’s happening right now, and what’s going to happen, but we often miss what just happened. And what just happened is still there, right behind us, and it’s still affecting us but it’s not in our field of vision. So we don’t realise that what’s just happened in the recent past is still active and still influencing what we do now. And that’s basically what priming is, or what I call “post consciousness”. These are the kind of metaphors I’m working with.

The reason we’re so focused looking forward is because we have to be ready for what’s happening next. We have to see what’s happening next. Even though it goes by really fast, we have to be anticipating and ready for it. So we’re sort of living in the future too, even though we’re in the present. The past affects us without our realising it much; we’re in the present but we’re thinking about the future and we’re anticipating the future. Those are the three time zones – the extended present really has aspects of the past and aspects of the future, but it all comes together in colours of the present. For example, our purposes or goals influence how we like or dislike things in the present.

The past affects us without our realising it much; we’re in the present but we’re thinking about the future and we’re anticipating the future.

One of the chapters in my book is called Be Here Now. It’s the title of the Ram Dass book published in the late 1960s – it’s the Buddhist idea of being in the present and the present moment. I start off with this example: I’m at home but rushing because I have a 10 o’clock Zoom meeting with Una and I’m running late. I need to get myself a cup of coffee first, but my dogs are in my way and I get mad at them as I’m under time pressure and rushing around. It’s because they’re frustrating my current goal. And my current goal is to get my coffee and get in my home office, but I’m being really rude to my dogs...

So, our current goal is to evaluate and respond to things as to whether they’re helping or they’re getting in the way of that goal. Even if they’re trivial goals, like doing something in the kitchen, if we’re under time pressure, we are rude and short with our family and angry with things that get in our way. Even inanimate objects – we yell at things if they don’t work, like if the coffee machine doesn’t work or it gets stuck... We’re yelling at a stupid, inanimate object because it is blocking our goal. So our experience in the present isn’t just what’s happening in the present – it’s how our goals for what we’re trying to do are being met or not, and that’s causing us to have emotional and affective reactions in the present that we wouldn’t normally have. I wouldn’t be yelling at my dog or a coffee machine, none of these things would be happening except for the current purpose and goal we have. And the current purpose and goal determines what we look at, it determines what we attend to, it determines what gets into our brain in the first place. So you can’t start with what’s out there coming in, like the behaviourists do; you have to start with (like William James and others have said) your purpose. Your current purpose drives what gets into your eyes and ears in the first place. You’re basically starting with the future – how it affects the present, how it affects how you feel.

And that’s what “be here now” is. “Be here now”, with mindfulness and all these kinds of things, is to detach from those influences because they’re colouring how you experience the world. And the world is not all about you getting a cup of coffee, and how you should feel about the world isn’t all about your current purposes. What you want to do is detach the future and the past from the present. Detaching the past from the present is very helpful in avoiding carrying your work life into your home life, or being unfriendly to somebody because so many people were unfriendly to you just recently, so you are unfriendly to the next person as if they’re the same person from before, but they’re not. Like road rage: somebody cuts you off on the highway, and then, over time, five or six more people cut you off, and you get really mad at that sixth person. But all that sixth person did was the same thing the first person did; they’re not the same person doing it six times, but you feel like it’s the same person doing it six times. And that’s not true. It’s summing up and making you madder at the end than you were at the beginning for the exactly same thing.

You have to separate that out, separate the future out; be only in the present, and do everything impeccably. Everything you do, do it impeccably – when tying your shoes, do it impeccably. That’s what I got from Buddhism; that’s what I got from Ram Dass. And the Dalai Lama, who’s so amazingly right about psychological things…everything he says in his tweets about Loving-Kindness and Compassion meditation and so on. That’s exactly right, and exactly what psychology science is finding. It’s not just nice, wise words that sound good – it’s actually true. He’s very informative, very knowledgeable, and if you’re going to follow somebody in the world, follow the Dalai Lama.

It’s funny how with science we are now confirming things that Dante knew but explained in a metaphorical way; and yogic science and Buddhism also knew these things. Now we’re just kind of putting science’s stamp of approval on it – as in, yes, it really is true.

It is, and, you know, the Dalai Lama to me is like William James, who wrote the amazing book The Principles of Psychology in 1890, before there was any science at all in psychology. He did it because he observed; he was an amazing observer. And an objective observer, not only of himself but of other people as well. Most of what he put in that book came from his own observations, logic, and everything else. I think it’s a very under-appreciated basis of knowledge about psychology and about people. It’s not just research and experiments in a lab, you know; it’s not surveys with hundreds of thousands of people, and self-reports about whatever – it’s being an observer, and being attuned and picking up through experience, always asking why people did what they did, and always trying to understand things. William James was very introspective. I think the Dalai Lama is perhaps not as introspective, but he’s also a keen observer, and thoughtful, and thinking about people all the time. For example, the best way to live with people is to cooperate, but cooperation doesn’t come for free. We don’t just easily cooperate with anybody, and they don’t easily cooperate with us. It comes from bonding and friendship. So you first have to bond and form a friendship to get to cooperation. For instance, little kids don’t just cooperate with anybody – they cooperate with those they have a bond with, like friends and siblings. They don’t naturally cooperate with just anybody – otherwise they’d wander off with a stranger and be killed. They don’t trust everybody, but the people they trust are the ones they cooperate with. You have to get the trust, and you get the trust from kindness, and you get the trust from warmth. There’s a sequence, and the Dalai Lama actually lays this out. He doesn’t say everyone should cooperate with everybody, and that all is wonderful. No, it doesn’t come for free; it comes from bonding and friendship, and that comes from trust and trust comes from warmth. And there’s a sequence there that he’s absolutely right about.

Why are dreams so important? In your case, you found the missing key in the relationship between consciousness and unconsciousness through your dream about an alligator and his white belly. It was your own unconscious process that gave you an answer to the question you had been working on for years – that unconsciousness comes first, and consciousness comes only after it.

It’s funny, I was just interviewed yesterday by a Yale student who’s writing for the university’s newspaper, and for an hour she asked me about dreams. The zeitgeist, again.

We tend to trust our dreams as if they’re a supernatural influence, like a premonition. So if I have a flight scheduled tomorrow, but tonight I have a dream about a plane crashing, often people will cancel their flight and not go because they think that this was a premonition or a warning about being on this airplane. The first thing about dreams is that they are an activity of your mind when your conscious mind is elsewhere. In the case of dreaming, your conscious mind is turned off. But as long as your conscious mind is elsewhere, there’s things going on in your mind that aren’t part of the conscious mind.

In the case of a hard problem that you’re working on and thinking about a lot, often, in the back office of your mind, an unconscious kind of problem solving is going on while you’re doing other things, like making dinner or talking on Zoom with somebody – it’s working in the background for you. Later, when you go back to it, you might have an answer. In fact, Sherlock Holmes, as well as many other famous characters in books, talk about how beneficial it is to take a break if you’re not making any progress. Do something else for a while and then come back to it, because what that does is allow only the unconscious kind of complexity problem solving to operate, and you might make progress and have an insight.

In the case of dreaming, your conscious mind is turned off. But as long as your conscious mind is elsewhere, there’s things going on in your mind that aren’t part of the conscious mind.

I often do this. I’m on my treadmill, or I’m going for a walk and I have these ideas. Of course, I can’t write them down, but I try to remember them till I get to where I can write them down. And it’s when you’re turning off your conscious mind that these things are still operating. I say this because dreams are an example of that basic case. When you’re asleep, your conscious mind is turned off; when you’re doing something else, like cooking or talking to somebody, it’s also on something else. And that allows problems to be worked on in the background. Lots of research has shown that unconscious kinds of problem solving is better for something that’s really complex because it’s better able to hold within it all the things influencing at the same time as compared to our limited conscious working memory, which can’t hold much more than two or three things at once.

I look at my alligator dream, and I look at the famous scientists who had similar dreams and breakthroughs. The dream told them the answer. So in my case, and the cases I’ve read about, you are consciously aware of the dream. In other words, the dream was a solution to a problem.

I think we can trust our dreams in that, if it’s important enough and an answer to a really important conscious problem, it will tell us. And if it doesn’t tell us, and we don’t remember dreams, don’t worry about it. It’s not like we’re losing lots of solutions in dreams that we’re not remembering, because unconscious processes are very good about breaking into our consciousness to tell us the answer to something we’re trying to remember. Sometimes you hear a snippet of a song in a store. What is that song? I know that song... And then later in the evening, boom, it pops into your mind and you remember who it was or what the song was. That means it was working on it all that time. When it got to the answer, did it just go away? No, it broke into what you were consciously doing and told you the answer. Regarding my alligator dream, I immediately woke up and had the answer, and it was deep and satisfying. I finally had the answer to a problem I had been trying to solve for ten years.

You know, people talk about “eureka” moments. Like Archimedes’ naked run from the public bath and down the streets of Syracuse yelling Eureka!, because the answer to the physics problem he’d long been puzzling over had suddenly come to him. It’s an exciting experience, and it’s definitely conscious. Dreams can do that for you, but do they come for free? Do I just start working on, say, the structure of DNA, and I’ll have a dream with the answer, for free, the next day? No, it comes because I’ve been consciously working on the problem for years. The activity of being focused on that one problem for so long is the mechanism, or the cue, for it to be also worked on unconsciously when your conscious mind is elsewhere. This can then result in dreams and these insights and solutions coming to you during mundane activities – such as for Einstein, while he was shaving. That’s what I feel about dreams. I think they’re wonderful, but they’re not unique. This is how the mind is always working on important problems. And it just happens that it got to the solution while you were asleep versus making dinner, or shaving.

My alligator dream was unbelievable, it really taught me something about myself. Because as soon as I had that dream, I woke up and realised that was the answer – I was basically done. I was totally demotivated; I didn’t even want to tell people I knew the answer. I had this amazing feeling of relief. What that told me was that this was a personal quest that I wanted to know the answer to. Not that I could now reveal this to the scientific world and publish a paper or something. I just lay there and realised the answer and how everything made sense. It was a wonderful experience, thanks to the dream, and when I tell people, they’re like, What the hell, an alligator flips over and shows you his white belly, and this is the answer to the big problem? But, you know, dreams can be silly; it clearly wasn’t about an alligator, and I clearly knew the message. Why was it an alligator in Everglades National Park? I haven’t even been there for 20 years...I don’t know.

I think if you can’t remember a dream, it’s probably not important. The ones that are important, you’ll remember, because the unconscious processes are very good at breaking into our conscious awareness when our conscious awareness is needed to solve the problem. Conscious and unconscious processes interact with and help each other. Just as when people are insomniacs, often they wake up in the middle night and they’re bothered by nagging thoughts of things that they need to do and they’re not doing. Again, it’s the unconscious, saying, You’ve got to do something about this. I can’t solve this problem for you while you’re sleeping. You’ve got to make the appointment with the doctor. You’ve got to go out for a job interview. You’ve got to mend relations with your parents. You’ve got to tell your father you love him. You’ve got to do what you’re not doing and nag, nag, nag until you do it. If it’s important, and your conscious awareness in mind is needed to do it, and it can’t be done otherwise, you’re going be nagged.

I think if you can’t remember a dream, it’s probably not important. The ones that are important, you’ll remember, because the unconscious processes are very good at breaking into our conscious awareness when our conscious awareness is needed to solve the problem.

It’s interesting that you mentioned those kinds of dark and very direct dreams, like a plane crash. I was not planning on telling you this, but I recently had a dream which fits directly into this category. I saw four of my funerals from my previous lives, and my funeral for this life as well. I also saw in the dream that I was on a flight to Amsterdam, and the plane crashed – no survivors. The thing was, I really was planning to fly to Amsterdam in three days. I was confused for a moment, but despite the dream, I took the flight and everything went well. However, as soon as I landed, I received a text from my friend that the day after I had the plane-crash dream, there was a real plane crash in Nepal. It was the country’s biggest plane crash in the last 30 years, and it was exactly the same route and the same airline I took some years ago on a trip to the Himalayas. I am still wondering if that dream was my subconsciousness, or was it something more – did I tap into something bigger that night...

Oh! In your case, I would trust your dreams and premonitions – don’t get on a plane if you have this dream. You know, you have to keep an open mind. Psychology, as a science, is really in its early days. We haven’t been doing psychology as a science for 1000s of years – it’s only for 50 or 60 years that it’s actually been an experimental method and all that; there’s so much we don’t know. And unfortunately, there’s a lot of arrogance that we already know everything – that there’s no new discoveries to be made, or what we know now is going to be true 100 to 200 years from now. And that’s wrong because if you go back 50 years and see what people said then, you’d laugh. If I go back 20 years and read what I wrote, I laugh. You know, it’s ridiculous. In the year 2350, they’re going to be looking back at my books and at what other people wrote during our lives, and laugh. So why do we think we’re going to be different – that in 2350 they’ll be saying, Oh, they were wise in 2023... Well, no; they’re going to be laughing at us already by 2073.

You’ve got to be humble and realise that we’re just doing the best we can, and we don’t know everything. Carl Jung also talked about synchronicity. He talked about people having the same coincidences and having the same thoughts. And I’ve noticed it; I’ve been writing them down. I’ve had it happen with other people – where, in a weird way, we have the same thought at the same time. And I’ve had an example with my daughter, and you have your examples. There’s probably something going on there. I don’t know what it is, but it’s not impossible. But to act like it’s impossible and just sneer at people who think it’s possible – that’s just intellectual arrogance. We’ve got to be more humble and realise that there may be something going on here with two brains and and how they communicate.

You’ve got to be humble and realise that we’re just doing the best we can, and we don’t know everything.

My colleague at Yale, Steve Chang [Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience – Ed.], shows that when two monkeys are watching the same thing going on, their brains get in sync. Their brainwaves become synchronised because they’re interacting or focusing on the same kind of situation – with rewards and things like that. This has been a known for humans for about ten years now – that when people are focusing on the same thing, their brains become synchronised. Well, that’s pretty mysterious and magical, right? And to have said that 100 years ago, people would laugh at you; but now with brain imaging and so forth, we can actually show this is true. So I keep an open mind. I mean, we’ve got to be open-minded about these things and not act like we know everything already. That’s just very arrogant.

You have spent over 40 years studying our unconscious and conscious mental processes. So my last question is, what is “I”? How would you define it?

Who am I? I think one thing I can add is that we own our unconscious processes. Oftentimes people use, Oh, I didn’t mean to do it, or, Oh, it was unconscious, therefore I wasn’t me, to gain distance. Usually we blame our unconscious processes for things that we don’t want to take credit for. In the meantime, we take credit for all the good things.

But especially in the case of goals and motives, the only way these goals and motives operate unconsciously is if you also have them consciously – they reflect your true goals and true values. There’s an old line by Kurt Lewin, a famous social psychologist from a long time ago: you can’t prime something that’s not already in a person’s head. This is a thing that I have to tell people all the time – you can activate from the outside only what’s already in a person’s head. You can’t give them goals and motives if they’re not already in there. So, yes, they could be triggered and operate unconsciously for that person. For example, the sexual harasser who is in a position of power over a secretary, and flirts or abuses that power. According to research, we can say: this is an unconscious kind of goal effect. Because power does that – it activates these goals and you don’t realise it. Well, not everybody abuses power. And the people who tend to abuse power have to have those goals in their mind in the first place for the power to activate. A lot of people react to power in a very selfless way. They become more concerned about the people they have power over. It’s like a parent with children – you have power over your children but you have their best interests at heart and you do things for them – it’s a more communal orientation. Power doesn’t corrupt everybody. Power makes some people more selfless and not selfish; it depends on what the goal is in their head that the power activates.

In all these cases, we own and are responsible for these unconscious processes, for the most part. We can be manipulated from the outside in innocent ways – to consume more, to eat too much, to buy products – and that’s because people outside of us know which levers to push. And that’s maybe different. But in terms of the motives and the goals, there’s no excuse to say that it was “unconscious” – there’s no excuse to be a racist, or to be a sexist and say these are unconscious biases – because there’s a difference between being a non-racist and being an anti-racist. And we can be an anti-racist, and we can actually have an unconscious motivation to be egalitarian and fair instead of racist, if we so choose. We have control over these unconscious processes. How they start, how they get into our head in the first place, and how they reflect our values. So we have to be careful what we wish for, because these things, once they’re in our head, can be activated from outside without our realising it. But that’s our responsibility. That means we own it. And I think that’s the most important thing I can add to this, because too many people are using unconscious bias as an excuse – saying that they didn’t mean that, therefore they’re not to blame. Our mind operates consciously and unconsciously, but all of it is our mind. We own the unconscious part as well as the conscious part – not just the conscious part. We’re responsible for all of it, to the extent that we can have better values and think about other people and be more empathic and not just be selfish. But that’s our choice. And that’s who we are. That’s the “I”. The “I" is both, not just the conscious part. People identify the “I” with only the conscious, the aware part, too much.