How do you discover 49 forms of darkness?

Sergej Timofejev

A conversation with the Indian filmmaker and artist Amar Kanwar about the obscure possibility of finding light in complete darkness

Amar Kanwar started his career as a director, and he is still making films; however, his films now spill over into complex interconnected narratives/installations that go on view at museums and art biennales. In 2022 his video installation ‘The Lightning Testimonies’ was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and in March this year, The Museum of Modern Art will also exhibit his 19 channel video installation , which was acquired for the museum collection, titled ‘The Torn First Pages’ (2004–2008). Before that, there were shows at the London Whitechapel Gallery, the Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris and New York and the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, among others; he also took part in four editions of Documenta (in 2002, 2007, 2012 and 2017).

It seems that Amar Kanwar’s films and exhibitions charm both art curators and viewers with their poetry and genuineness, despite the fact that he tends to choose subjects that are quite difficult and controversial. Born in New Delhi in 1964, the Indian director and artist made films where his protagonists or the author himself discussed problems of labour and gender, violence and justice, rights of indigenous peoples, religious fundamentalism and ecology. But they were never pure documentaries; Kanwar described his method as ‘poetry as evidence’.

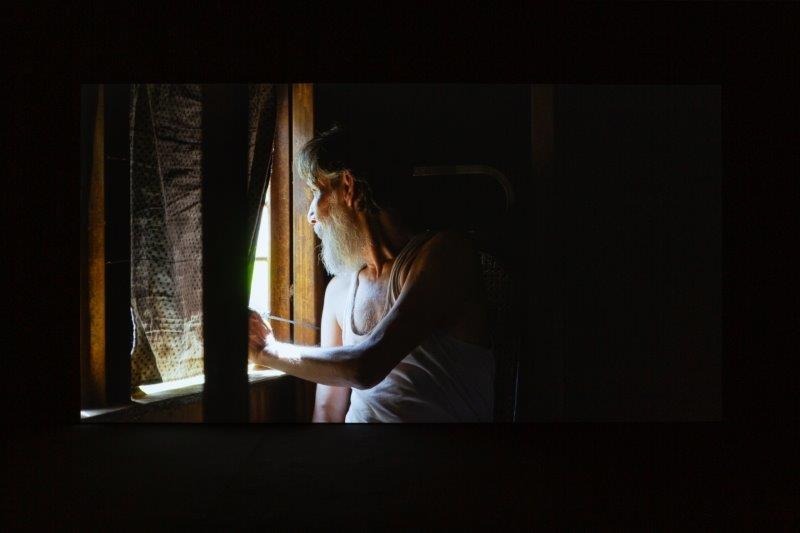

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning. Exhibition view at the Ishara Art Foundation / Dubai, 2020. Photo: Ismail Noor | Seeing Things

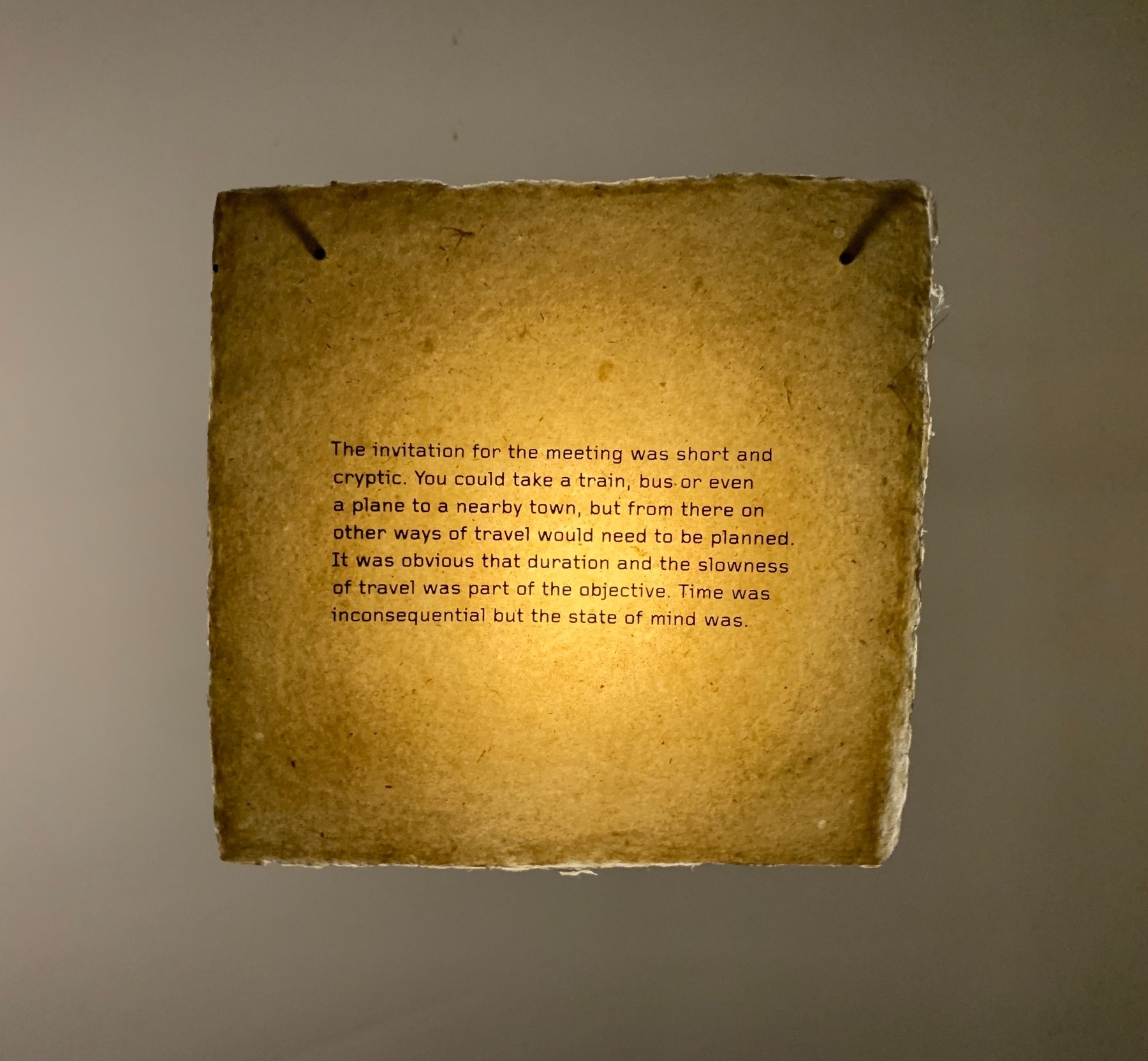

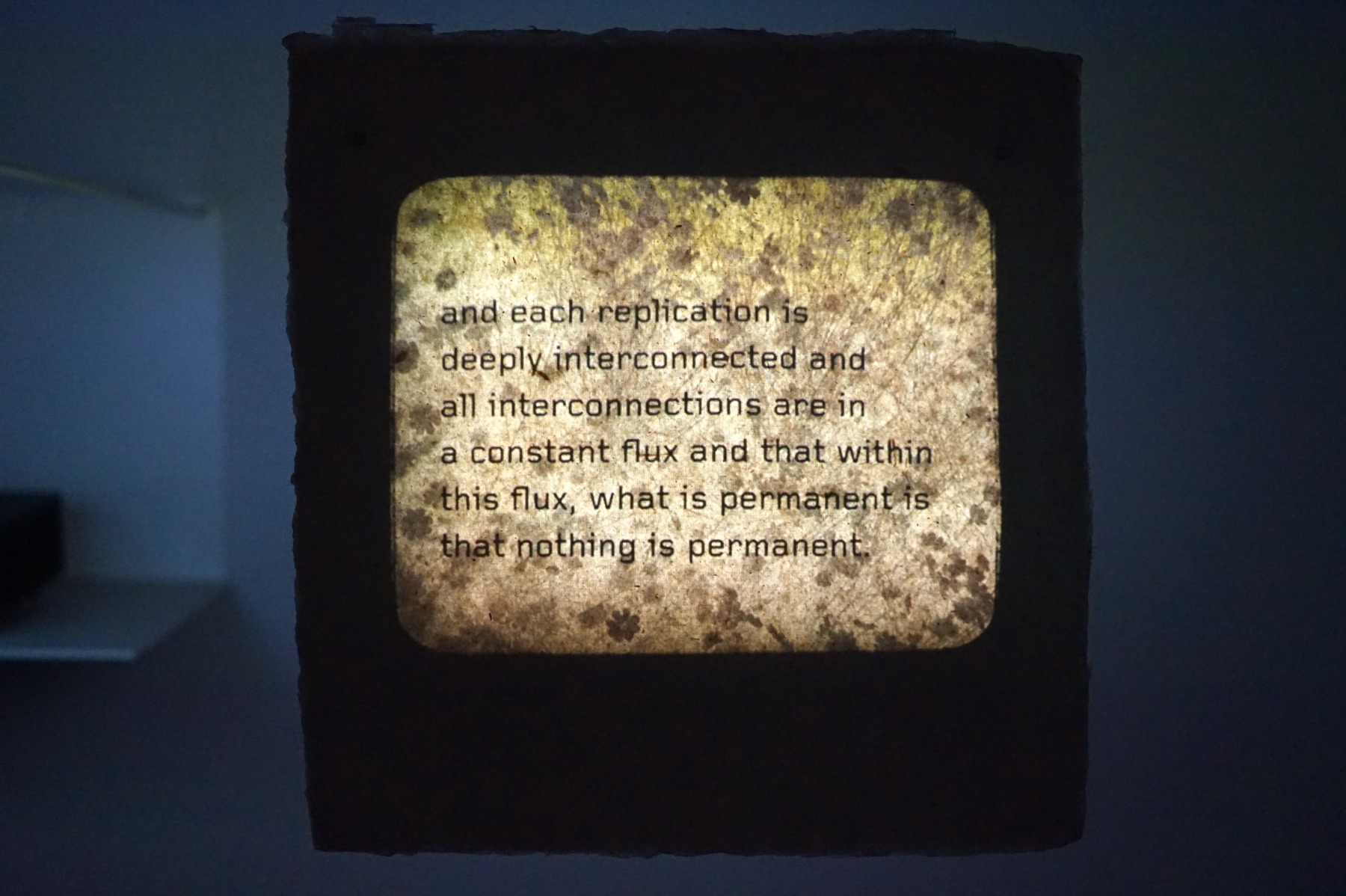

And yet something like a philosophical shift has taken place in his artistic approach. It has found its expression in the film and exhibition project ‘Such a Morning’ that was first shown at Documenta 14 in Kassel and Athens and then went on to tour the world, from Paris to Dubai. The project also made its way to the Indian city of Kochi, where it was shown as part of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale curated by Shubigi Rao and initially scheduled to open back in 2020. The pandemic forced a change of plans, and it was only in late December 2022 that the exhibition opened its doors to the first visitors. And it was there, in two enormous rooms of the Anand Warehouse building (one of the string of vast trade warehouses that were transformed into venues for the biennale) that I saw Amar Kanwar’s works. One of the rooms hosted a screening of an 85-minute film where the protagonist dedicates himself to exploring darkness and silence; in the other, the walls were lined with numerous projections on backlit uniformly sized sheets of handmade paper, now showing fragments of text, now – photos of plants or indistinct patterns. Sometimes the projected images would move, like the small black bird that suddenly came to life and then froze again.

‘Kanwar has created that miraculous kind of work that anyone can read but that also, crucially, defies interpretation,’ Ania Szremski wrote in her review published in 2019 in the Artforum Magazine. To be precise, it lends itself to a multitude of interpretations, all of which turn out to be linked – in one way or another – with the possibility of finding light amidst almost complete darkness. And that is exactly the kind of situation in which many of us have found themselves in the 2020s. Is there any point in this pointlessness? Is the world around us falling apart? How do we stop this destruction?

Amar Kanwar at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

These issues are what we spoke about with Amar Kanwar, and for this conversation we left the warehouse building to enjoy the waterfront view: the salty and warm Arabian Sea washes the beaches of Fort Kochi, the district of the city that plays host to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale time and again. Amar, a bespectacled medium-height man sporting a dark beard, was smoking cigarettes of the Indian Kings brand. He spoke in an unhurried way, watching the water; occasionally the conversation was interrupted by workers who would emerge from the building to saw something off of something and then disappear again. We paused during these interruptions and then went back to the conversation centred around the ‘Such a Morning’ film and exhibition and the current times when so many ideological and social constructs seem to have lost their meaning.

How did this project start?

This work began with the film that I showed in Kassel and in Athens during documenta 14. Starting from around 2015, I had been feeling a need to step out of everything I was doing. Most political or social systems were not offering valid solutions to the predicament that we were all in; most ideological templates or positions available seemed caught in their own traps. Also, we have seen what happened to Syria. There is no explanation; there is nothing more to know or say after Syria. We have seen this in so many countries, and now again in Ukraine. It wasn’t making any sense. So, in a way, that’s the impulse for this film – a need to prepare for what lay ahead, to find a way to prepare for even considering a restart. I felt the need to step back – so that one could see the blind spots that one is not able to see.

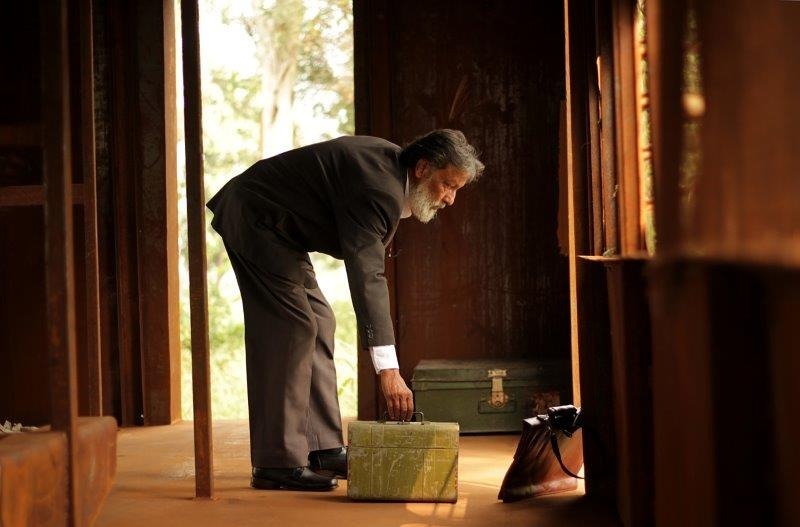

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2018. Video still. Photo: Cathy Carver. Courtesy of the Artist And Marian Goodman Gallery, NY

And that’s how the film happened. In the film, the main protagonist is an old professor… there are actually two – a man and a woman, but she appears later. The story begins with a professor who withdraws from his work and life, and disappears. There is a lot of speculation and discomfort about the reasons for his disappearance. Several theories are suggested by his colleagues, but the speculations continue. Some finally believe that he is living in an abandoned train carriage in a little forest on the outskirts of the city. It seems he has covered up the inside of the train compartment and is living there in complete darkness – so as to prepare, to acclimatise to darkness before the full darkness arrives.

As time passes, the professor experiences a series of hallucinations and epiphanies, and then, eventually, a new character emerges: a middle-aged woman, armed with a rifle inside her house as if almost eternally on guard. Days, months pass, perhaps even years go by, until one day a group of men, workers, suddenly appear and begin to dismantle her house, piece by piece. The experience of this hallucination is compelling, disturbing, and in many ways, triggers a series of reflections.

Following this, the professor comes out of the train carriage and writes a series of letters to his university chancellor, students and colleagues. The professor identifies 49 forms of darkness and informs that to teach any further, more research is needed on each of the 49 darknesses. And then he writes his last letter, which is the seventh letter to all of us, in a sense, and which is almost like an invitation to come together to study, share, listen and restart thinking.

Darkness here is not looked upon as something negative. It’s just understood as something that has potency – that you can get into it and stay and learn to look and think in different ways again.

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning. Exhibition view at the Ishara Art Foundation / Dubai, 2020. Photo: Ismail Noor | Seeing Things

To look into an area we hadn’t looked into before…

Yes. There is always one truth – that you can see in daylight. And there is another truth – that you can see in darkness. So what could be the vision from the heart of darkness? How does that vision translate? How does it prepare our mind, our body, our way of looking, thinking, listening? So, even before we start saying that we should do this or we should do that, this work really was about stepping back and preparing, and then trying to come together to restart.

But do you feel that this restart is still possible?

I feel that the kind of situation that we are facing in the world – when almost nothing makes much sense…when you think that humans would understand that this is actually the right time to correct our ways of living, but we go ahead and do the opposite…when we can clearly see the value of conserving, but we destroy. So, it’s very clear that nothing makes much sense or has meaning.

But what I feel is that this is not the first time in human history, or the earth’s history, that we have come to this point. And that there have been many people before us, hundreds of years before us, who have put great thought into this. There are many traditions – indigenous traditions, spiritual traditions, philosophical traditions, intellectual traditions and histories – that have put great thought into the meaning of our meaninglessness. And this thought is quite sophisticated and very intelligent. It offers many ways to think, to proceed, to recalibrate, to reconceive. And this is not the first time that we have faced this kind of madness in terms of sense, or rather, loss of sense.

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2018. Video still. Photo: Cathy Carver

Maybe just the scale of this madness is unbelievable.

We have now moved into this digital age. And what this digital age does is that, apart from allowing people and organisations to manipulate us constantly, it makes us aware – 24 hours a day – of the scale of this madness. Which does not mean that this scale of madness did not exist before. It existed. But we have access to it round the clock, and in great detail, from continuous sound, image and text, which is why there is also this heightened perception of a loss of control, of uncertainty, that things are apocalyptic, and so on and so forth. But perhaps it isn’t. For me, personally, it’s very clear that there are some very beautiful traditions that teach you, or that help you, rather. And these are not religious traditions alone; there are philosophical traditions as well that equip you, I would say, in how to live in the centre of the apocalypse that is us.

Amar Kanwar. Exhibition 'Such a Morning' at the Anand Warehouse / Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022-2023. Photo: Vladimir Svetlov

So, it’s more about finding your own personal balance than about “saving the world”?

When you look at the world around – which is supposed to be in need of saving and which is disintegrating – one of the first things that you can see, apart from the disintegration and the violence, is that there has been enough evidence of this disintegration for quite some time; this is openly and clearly available for everybody to see. So, if we have access to the evidence, and yet we continue to disintegrate and destroy, then there must be something wrong in the way we are processing this. Or, maybe we are looking at the “wrong” evidence. Certain kinds of evidence lead to one kind of understanding. Another kind of evidence can lead to different forms of comprehension … but that is another discussion.

However, it is quite clear that while there are many people who are not in favour of violence and destruction, there are also many people who are in favour of it. So, some people are in favour of violence, some people are against violence. But actually, we find that there are a lot of people who are both against violence and for violence at the same time. So you can have the nicest man be very gentle and peaceful in one part of his life but brutal in another part of his life.

What does this mean?

I said this because I think we have reached this point. If we look at Syria, if we look at COVID, and then post COVID; if we look at Putin and Ukraine; if we look at India, for sure, it’s clear to see where we are – we are now supposed to be seeking revenge, advocating and justifying violence and discrimination in response to invasions that happened a few centuries ago. Nothing seems to have existed in the several hundreds of years before the invasions; there is no complexity in the study of the past or the present. It is acceptable now – this desire for vengeance and assertion, and therefore, a new identity of self, community, religion, and nation. Our level of absurdity, and the pain caused from it, is also very deep. I think we have once again reached the point where we have to come face to face with the fact that when you’re talking about saving the world, or trying to do anything in that direction, it’s necessary to also address the inner self. I think that’s where we finally are, whether you look at Afghanistan or Pakistan, the Philippines, Russia, Ukraine… wherever.

And if you work on the inner self, the world around you does become better. I think that when you look in a certain way, there is great meaning in meaninglessness. It’s just the way that you understand the inner workings of one’s own mind and how you address it, and how you comprehend that – how you comprehend life, how you comprehend relationships between various beings. All of these things actually add up and also have great potency for change.

So, without inner change, we cannot ask for societal change?

I’m only pointing out that I find it very interesting to see that there is a lot of work and thinking being done that is very sophisticated – philosophical as well as psychological – that addresses this: the inner self in relation to the outer self. And if this exists, there is no reason to reinvent. New solutions need to be able to gain and build on from previous understandings and insights. Because the kind of crisis that we are facing is not new. The desire for brutality is not new. That pleasure from brutality is very old. Self-destructive narcissism is also not new. The delusions that arise from arrogance are ancient.

And this has been understood and thought about. I think it’s interesting to look at people in the past and how they resolved this. They did not just think about it and say, there is no hope – in fact, they found many ways to address it that are very interesting. I keep using the word “sophisticated” because they’re not simply metaphoric. They’re not just esoteric – they are also very rational, sophisticated and consistent.

Amar Kanwar. Exhibition 'Such a Morning' (Letter 7, 2017. Detail) at the Anand Warehouse / Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022-2023. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Could you name some of these people from the past who were able to solve such problems?

The historians, political theorists and philosophers are there, and there is much to learn, but I am not a scholar. I think with my feet. I keep going to people and request clues with which to address the repetitive pain, dilemmas and contradictions of the inner self. Repetitive and relentless across races, ages and time. There must be a reason why we are the way we are. There must be a way to comprehend.

Sometimes they have pointed me to older Buddhist texts on Shunyata/Emptiness, or to ancient Yoga texts that analyse the mind along with the body, giving very useful and interesting insights and templates. At times it is the 15th-century poetry of Kabir that provides the answers. Or it could even be the Katha Upanishad or the Tibetan Book of Natural Liberation through Understanding in the Between! Or stories translated from the oral traditions of various indigenous communities – their stories of lived lives, of multiple beings, of their traumas and wisdoms. There is no end to it; you soon realise that they are all talking about the self, the mind, and it’s the same map of mind-body-earth-and-universe around us. Perhaps all in a context of healing? Maybe for a deeper understanding through learning, through critical reflection, through mind-body awareness, through silence and so on. Soon you realise, or at least I begin to see, the threads of experimentation and analysis; it is obvious that they are all dealing with the same pain and confusion of our existence and the need to address, respond, repair, resolve, reorient … it’s like a process of continuous honing of the mind-body self with a spectrum of tools. And these tools are intelligent, complex and useful, and they work as well.

Amar Kanwar. Exhibition 'Such a Morning' at the Anand Warehouse / Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022-2023. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

You often use text in your work by mixing it with other mediums. How does the text “work” for you? Why is it meaningful to include it in your works?

Some of my earlier films were with no text but with voice. They were essays, and they had extensive use of voice.

A narrator?

Yes. Spoken voice. Often my own. I thought that we need to speak, we need to enter fully the world of spoken poetry, in a sense. And then I stepped back from that; I thought maybe we needed to listen. Later, I felt that maybe we need to leave this voice alone and get into silence. Get into text and silence – texts that were written words along with texts that were written but unspoken thoughts. And then, maybe only looking – perhaps a certain way of looking leads to a certain kind of comprehension, which then leads to a certain kind of compassion. In a way, I feel like with almost every film I’m stepping back…stepping back, trying to get to this point where another set of senses can come into play and it becomes possible to comprehend. It’s like I’ve been making the same film again and again for the last 25 years.

And I’ve been addressing the same issue for the last 25 years. I’m trying to comprehend exactly the same questions that you just asked. But with every work, I try another way in which to comprehend. Sometimes I do an exhibition where we have a spectrum of ways to comprehend everything being presented together. And it’s not each separate way but the transition – from one form of comprehension to another form of comprehension, and to yet another – in which they are all actually trying to comprehend the same thing.

But it is your experience of moving from one kind of comprehension to another kind of comprehension, and then to another kind and so on. You do realise that you are understanding the same thing, but in a short period of time you are understanding it with different tools and different senses. And each understanding is of a quite different quality, even though you’re trying to understand the same thing. These transitions are also extremely joyful; they are optimistic, they give you strength, they make you want to live and act and be and create and do many things in the world – as a visitor, as a viewer, and not just as a maker.

About text and image – it’s the same thing, I’m just redoing it. In this film, for instance, there is a text, the story finishes in the film, but then the story continues outside of the film, and the main protagonist carries on writing even though the film is over. The last letter that he writes is actually almost like a call for collaboration. Sometimes people respond to that call. And then the story becomes a collective process of research. And then it becomes something else – it becomes physical and personal, and so on. And so become many things over time. Maybe you or someone else in Kochi will want to take one of the 49 darknesses further. Who knows what we may discover then?

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2018. Video still. Photo: Cathy Carver. Courtesy of the Artist And Marian Goodman Gallery

This main protagonist, a mathematics professor – is there a real person behind this character, or did you just come up with the idea of him?

Actually, it’s he and she, and they are us. If you look at your own life, you will feel that there is a part of you that wants to step out and get into isolation and find a pause to figure out how to live this absurd existence.

Then there is another part of you – if you look at her, you can be her as well. When you see that in front of your eyes, your entire world is disintegrating. But you are not sure whether that disintegrating is happening in the present, or if it just happened a little while back, or is it something that you are expecting to happen. Right? So you can be her, you can be him, he can be her, and she can be him as well. So when you have a situation where so many possibilities are viable, then this terrain is very potent. It becomes potent for inferences, insights, revelations, instinctive intuitions, understandings of different kinds. She could be reading a book about him. He could be having visions of her.

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2018. Video still. Photo: Cathy Carver. Courtesy of the Artist And Marian Goodman Gallery

Everything is interconnected…

Everything is interconnected, everything is valid. And so in that sense, it’s not a terrain that we are accustomed to in terms of thinking in that way. So what this story does to you is that it takes you into a zone and opens up varied interpretations and different senses. So even if somebody may say that she’s getting destroyed, another person may say that actually she’s getting freed. She has been protecting herself and her house forever, but now that the house is destroyed, she’s free. I mean, these are two totally opposite positions, and both are quite valid. So, how are they valid? And what is more valid for you? How do you interpret her? What is this vision that he sees of her? What do we get out of it, et cetera, et cetera. So, when you read his letters and you get to the seventh one, you find many examples. It’s a speculative meeting, a speculative gathering where the first item on the agenda for discussion is the question of “maybe”. They discus “maybe”. It’s very interesting...what does “maybe” mean? It opens up so many possibilities and philosophical, metaphysical, intellectual and spiritual positions. And they are not new; if you go back, you will find traditions that have deliberated on the question of “maybe” and have written about it as well.

So, how do we relate to this? Various items are listed in such a way that the juxtaposition of the first with the second, the third, the fourth (and so on) starts throwing up different ways of thinking. The intention is not to advocate another template but to simply open one’s body, being, mind and heart in many different ways – a certain kind of preparation even before you begin anything.

Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2018. Exhibition view. Photo: Cathy Carver. Courtesy of the Artist And Marian Goodman Gallery

In my mind, what we are speaking about also connects to the line that became the motto for the 5th edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale: “In Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire”. For me, ink is the tradition of writing – the culture of written texts, of written thoughts.

You know, there are volumes of knowledge and consistent intellectual exploration – as well as artistic expression, literary expression, and poetic expression – that existed without a script for a very long period of time. This is the memory/oral tradition, and it has expanded and exists even here, where we are sitting. It still definitely exists outside the written or printed word, but has great value.

But if it’s not written down, how can you connect to it?

Rather than me answering, the most exciting way to answer that question would be if you take the following sentence:

I have heard that there is a lot of literature and knowledge that exists, but it has not been written down – how can I find it, get to know it, and connect with it?

Write this on a piece of paper in the Malayalam language, walk down the street outside and present this question to whoever is willing to answer. All who answer will show you a route and method to connect to that. They will not say, “What are you talking about?” They will not be confused; they will say, “Of course!”

They will naturally respond…

Yes. And they will tell you, “You can do it like that”. The next guy will say – “You can do it like ___”, and so on. They will all show you a different route to it.

Amar Kanwar at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Well, it’s my last day here, so maybe I’ll come visit again, and then I’ll walk down the street with this piece of paper. [Both laugh]

Yes, I hope it will be a better visit when you come again.

Thank you so much.

Title image: Amar Kanwar. Such A Morning, 2017. Photo: Cathy Carver. Courtesy of the Artist And Marian Goodman Gallery