The Cosmos does not care, and that is beautiful ‒

Sergej Timofejev

‒ according to Polish artist Katarzyna Korzeniecka

During the most significant event of the Warsaw art scene – the Warsaw Gallery Weekend taking place in late September and early October ‒ the Gunia Nowik Gallery opened a show by Katarzyna Korzeniecka. Selecting the artists presented to the public during this time is not a thing treated lightly by Warsaw art galleries, since everybody and his dog in Warsaw spends Friday through Sunday wandering from one art space to the next one. Last year saw Gunia Nowik place her bets on the current enfant terrible of the Polish capital’s art world, the young painter Jakub Gliński, who has borrowed extensively from the culture of graffiti and street art. This time around, she has chosen an artist whose name may not be on everybody’s lips and who works in techniques that non-specialists may not have heard of ‒ ebru (paper marbling) and marquetry. Marquetry is a special wooden mosaic technique; the definition of ebru is a technique of drawing on the surface of water and transferring the resulting image to paper or another solid medium.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka at her studio. Photo: Szymon Rogiński

The alchemy of floating paint on the surface of water into which huge sheets of paper are then dipped creates layers upon layers of colour, producing, as the paper is first left to dry and then submerged into water carrying swirls of another colour, quite astonishing cosmic landscapes. The cosmic theme is also present in Katarzyna’s wooden mosaics, as it is in the title of the exhibition (on view through 19 November) ‒ Thea. Thea (or Theia), of course, is the name of the hypothetical protoplanet that made a significant impact on the development of Earth and the emergence of life on it.

“4.5 billion years ago, a rocky protoplanet, twinned with Earth and slightly smaller than it, formed in the young Solar System between Venus and Mars. [...] As Thea increased its mass, gravity brought its orbit closer to the Earth’s track, followed by the inevitable collision. Thea’s mantle broke into pieces and her metallic core overflowed into the centre of the Earth. Layers of liquid rock, dust and gas mixed, and in the swirling disk of matter, the present-day Moon was created. Formed in this fashion, lacking its own heavy core, the satellite does not revolve around its own axis, as most celestial bodies do, but revolves in a circular motion around the Earth, always facing it in the same direction. The Earth–Moon system, unique on a cosmic scale, has created completely unique conditions on our planet. The Earth’s vast, hot core enables plate tectonics – the continuous movement of the Earth’s crust and the drift of continents. The Earth’s axis, skewed as a result of the event, guarantees the phenomenon of the seasons, as well as the polar day and night. Large and close to the planet, the Moon stabilises the position of the Earth’s axis and at the same time its climate, while the force of its attraction generates the tides of the oceans. Hot after the collision, the satellite orbited much closer to the Earth. It is now moving away from us at a rate of 4 cm per year. Four billion years ago, the proto-ocean was therefore subject to even stronger tides. Large areas of land underwent a cycle of continuous flooding and drying, which enabled the synthesis of the first amino acids and the emergence of life. Had young Earth not swallowed her sister’s metallic core, she would probably never have become fertile,” says the curator of the show, Agnieszka Tarasiuk, in her essay.

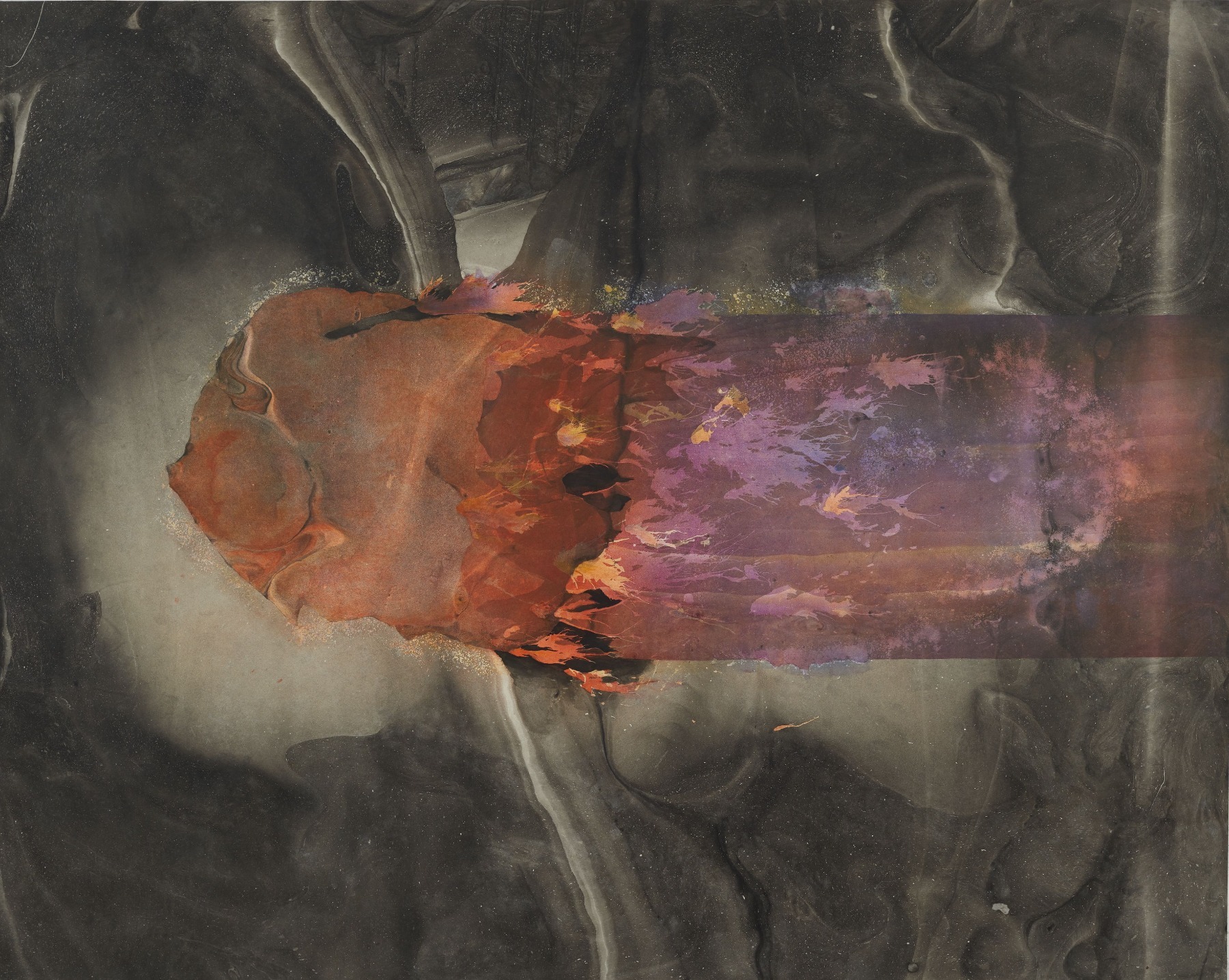

Katarzyna Korzeniecka. Untitled. 2022. Own technique based on ebru on cotton paper. Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

She also presents an intriguing description of the natural roots of ornamental abstraction: “The same physical phenomena that maintain the movement of granite landmasses on the basaltic crust allow ornamental images to emerge. Originating in China, the technique of transferring patterns created on the surface of water onto paper takes advantage of differences in density, surface tension and gravity. Fields of colour swirl and circulate on the surface of the water, collide with each other and separate like continents on a globe. All one has to do is take them off the surface of the water by applying a piece of paper [...] to it. The oldest marbled papers date back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907). From China, the tradition moved to Japan and, along the Silk Road, to the Mediterranean. To create Japanese suminagashi, one needs only paper, water and ink. The Middle Eastern Ebru requires more ingredients. [...] Ebru flourished in the Ottoman Empire as a method of creating meditative images. In Sufi sects, abstract pattern-making was practised as a path of self-development. In the 17th century, the technique of paper marbling reached Italy and became part of the Middle Eastern heritage in Western Europe, but the ornaments, devoid of the spiritual symbolism of Islam, were treated as a purely decorative element. Thus they hid on book covers and objects meant to pretend to be marble. Abstraction had to wait until the 20th century to be recognised by Northern and Western art.”

View from the exhibition "Thea". Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

The curator sees another reflection of the fundamental principles of fractal geometry in Katarzyna’s works: “Thanks to the discovery of fractals, it is possible to mathematically describe and prove the principle of similarity in the shape of galaxies, continents, trees and corals, as well as in the layout of the lungs and the circulatory and nervous systems of vertebrates. Fractal geometry is deeply inscribed in the structures of the mind…,” she concludes in her essay.

While every artist must work with some kind of material, water and wood are really genuine natural elements of this world we live in. Gunia Nowik, the gallerist responsible for the first solo show by Katarzyna Korzeniecka in eighteen years, told me that the artist’s family has a very special relationship with water. It is about this connection and the Cosmos within and without us that we spoke while perched on the windowsill of the library at the Warsaw Museum of the Earth housed in the ancient masonic Willa Pniewskiego in Na Skarpie Boulevard.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Cosmos, 2011, marquetry (various kinds of wood). Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

I heard that you have some Georgian roots.

Yes. That’s true. My great-grandfather was from Georgia. He came to Poland 100 years ago and decided to stay here.

He was escaping from the Bolsheviks?

Exactly. He was a young prince from the aristocratic family of Kurulishvili. He moved to Poland because his older brother already lived in Warsaw.

I also heard that one of your close relatives was a person whose profession was looking for water, finding it.

Yes, my father. He passed away last year… He was looking for water as a dowser.

That was his profession?

He was educated as an architect. Later in his life he discovered that he had a special gift for looking for underground water. So he would go and look for places where people should make wells.

How did he discover his talent for this?

I don’t remember exactly how it happened. But I remember him walking with a branched stick. When he finally found a place with water, the upper part of the stick would rise or move somehow. At this point he knew who deep down the water was. I don’t know how it worked – it was just magic for me.

To know how deep the water is? This is the first time I’ve heard that there are people with such an ability...

I think he was a kind of modern shaman. Maybe that’s the explanation?

Was he looking for and finding water like that here in Poland?

Yes, mainly in Poland, but also elsewhere.

And do you yourself feel some kind of personal connection or relationship with water?

Of course I do. I work with water, in a slightly different way. But not only with the Element of water. I feel like a particle of nature. I’m part of the Universe.

View from the exhibition "Thea". Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

Did this relationship start at the very beginning of your career as an artist, or did it appear later?

It came with time; it was not evident from the beginning. Maybe I could find something like this in my first works, but then I lost it somehow, especially during my studies at the Academy. I was doing photography. I was interested not only in capturing the time itself in photography but also in the process: the darkroom, the water, and the different ingredients.

And then a significant change happened in my private life – I became a mother. That changed a lot in my artistic life. I had always heard that women artists couldn’t be mothers, but I didn’t know why. So, unfortunately, I discovered why. (Laughs) And it was not because of my child or me, but because society rejected me. It was strange: “You are a mother, okay, so we will not interrupt you – stay there”. And at the beginning, I didn’t understand what was going on, but after two years, it became more and more painful for me as an artist. Yet throughout this time, I was doing something for myself; I was always looking for new directions, trying to do things differently. I was still experimenting with photography until my studio burned down completely. Then I thought – maybe that’s a sign. I started exploring a new technique. I looked at the structures of wooden panels searched for shapes in them, and they reminded me of the planetary pictures of outer space, like NASA pictures released around 2009. I felt that was quite similar – what I could see on those NASA pictures and small areas of various kinds of wooden furniture. So I started to collect those pieces and made these kinds of "cosmoses" and "universes" at my kitchen table. Then I began to look for something lighter – easier to work with in a home studio.

I was interested in different kinds of paper, like inside the old covers of books, so I started to look at how to make this kind of paper. I didn’t even know at that time the technique’s name. I met with some old craftsmen and asked them, but according to them, it sounded like a legend — forgotten knowledge. I found the traces in an old bookbinder’s handbooks; the papers I looked for were similar to the Turkish ebru technique. I eventually developed my workshop – making paints from pigments and practising with water. I knew the colours should be very light and the water should be heavier, and I had to find a balance between them.

That was the beginning. It was a long process that took me many years until I finally achieved the right effect and opened a constant dialogue with the water Element.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Untitled (Sun), 2022, own technique based on ebru on cotton paper, mounted on a stretcher bar, 140 x 90 cm. Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

So you also use paper…

The paper is significant because It’s an integral part of an image in this technique. It’s quality paper with minimum additions. Paper is at the same time a very delicate and tough material. It has to be strong enough to resist the power of the water during the long process of making a picture. And I have to make it completely wet again to fix the image on the stretcher bar.

And you put the same paper in different mixtures of paint and water.

I work on the surface tension of water. It depends on how big the paper is or what I want to do with it. In the exhibition you can see a two meters one. That’s my biggest size for now. I paint on the surface of that size. Then, I take off the picture directly from the water - put the paper on the water for just one second and then take it off.

But then you repeat the process with other paints and water to make more layers.

Yes, I work with layers. With every layer, I have to wash it out, dry it, prepare new paint and water, and then do the next layer. The works in the exhibition have some eight or ten layers.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Untitled (Meteorite fall), 2022, own technique based on ebru on cotton paper, mounted on dibond, wooden frame, 188 x 150 cm. Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

And how much time did it take you to make Meteorite?

About three weeks.

Did you have a concrete idea of what you wanted to achieve?

Yes. It was a childhood memory – I was lying down on the ground in the countryside, looking at the night sky. Suddenly, I saw a meteorite flash across the sky. And that’s it. I tried to paint a picture of it – I think it captures my memory quite well.

Is this a very significant memory to you?

Of course. It was impressive!

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Untitled (Meteorite), 2022, own technique based on ebru on cotton paper, mounted on dibond, wooden frame, 150 x 188 cm. Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

Was it a small meteorite or a big one?

It was the size you can see in my picture. It was huge! The next day I heard on the radio that a meteorite had fallen down in France. It was like a ball of fire going through the night sky. It was incredible.

Do you look at the sky often?

Yes. (Laughs) Very often.

Do you feel some kind of a connection to the cosmos?

Yes, I feel a strong connection with the Universe and Nature. A direct meeting with the Meteorite was my turning point in understanding the human condition.

Are you a religious person?

No.

But how do you think it all started? The whole cosmos?

I think it has always been there – in some different way or in the same way – we don’t know. We just know how small of a percentage our knowledge of the cosmos is – even about what is going on right here on earth, like quantum physics. I think we know practically nothing about it, but scientists have just discovered something that humanity has always sensed.

Do you like to read books about physics and the structure of things?

Yes, I like it a lot.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve learned from these books?

The latest such thing became the title of my exhibition - the Thea story. In the beginning, there was a planet similar to Earth, and quite close to Earth. Scientists have named it Thea in honour of the mother of Selene from the Greek mythology. It collapsed and one part of it became the Moon, and another part of it smashed into the Earth and is still there – inside the Earth, as a part of it. It’s an incredible story! This event changed Earth’s orbit by 23 degrees. Now it circles around the sun with this changed position. And that’s why we have changing seasons and the climate we have, and it’s also why we are here.

Because of Thea!

Yes, and it’s changing a lot!

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Untitled (Big Bang), 2022, marquetry (various kinds of wood), ø 80 x 2 cm. Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

But you are also still making these works from wood…

Yes, I returned to marquetry last year and made one about the Big Bang, about this big collision. It’s a kind of illustration of that particular moment, but simultaneously you can see the middle of a trunk tree. I wanted to show this connection – a tree also has a kind of "Big Bang" of the Universe inside it. Inside every tree.

And this square work?

You can see a galaxy nebula through the shapes inside trees: smoke, mists, and all of the mess that is inside the Universe.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Cosmos, 2011, marquetry (various kinds of wood). Courtesy of artist and Gunia Nowik Gallery

Yes. It’s there. (Both laugh). Did you use pieces of wood from different countries?

Yes. There are small pieces from different trees from all over the world. I look for them in different places, even in the trash, appreciating the materials because of the unique “drawings” within them.

Are there any new materials that have grabbed your interest lately?

I think I’m more into large-scale work now, and after this exhibition finishes, I will go back to the water-box in my studio to do next large-scale work.

Last question: why are we here, in the cosmos?

The most impressive thing is that we don’t know and that it can be because of an accident, for no reason!

It was just Thea! (Both laugh).

Yes. Just because of this collision! I hope there are more accidents somewhere else in the Universe, but we don’t know where and of what kind.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka at her exhibition at the Gunia Nowik Gallery. Photo: Szymon Rogiński

So we are like watchers, people who are viewing the cosmos? May be that is our mission?

Maybe.

Or perhaps the cosmos doesn’t care if we’re watching or not?

Of course. The cosmos absolutely doesn’t care! (Laughs) Only we care about it. And we think that we are important somehow, but the cosmos doesn’t care at all.

It’s sad but also beautiful.

I think it’s beautiful! And there is nothing sad about it.