Humans are tricky animals

Una Meistere

An interview with British artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

British artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s work focuses on humanity’s complex relationships with nature and technology. Having studied architecture at the University of Cambridge and obtained a PhD in Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art, Daisy's work – which is often a collaborative project with scientists – explores subjects as diverse as artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, exobiology, conservation, biodiversity, and evolution. She is the lead author of Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating Synthetic Biology's Designs on Nature (MIT Press, 2014), and exhibits internationally, including at MoMA New York, the Centre Pompidou, Somerset House, Royal Academy, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

In 2019, in collaboration with smell researcher and artist Sissel Tolaas (whose work was also shown at the first Riga Biennale of Contemporary Art, RIBOCA1) and an interdisciplinary team of researchers and engineers from the biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks led by Creative Director Dr. Christina Agapakis, Ginsberg created the project Resurrecting the Sublime. Using synthetic biology, the project reconstructed the smell of three extinct flowers lost due to colonial activity. At the same time, it asked the question – will we ever again smell flowers driven to extinction by humans? The project was first exhibited at the Center Pompidou last February. Ginsberg’s most recent projects also include the video installation The Substitute (2019), which was inspired by the widely reported death of Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros, in the spring of 2018. The work raises an awkward question for humanity – we mourn the death of the rhino, yet driven by the desire for the imagined life-enhancing properties of its horn, we have done everything to promote the species’ extinction, while simultaneously rejoicing that one day it might be brought back using biotechnology. In the video work The Substitute, a northern white rhino is digitally brought back to life, informed by developments in the human creation of artificial intelligence.

My conversation with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg took place via Zoom. At the time, the pandemic lockdown was still in place in the UK and Daisy was in the countryside, an hour's drive from London and considering not returning to London even after the lifting of lockdown. Since her next project is related to the plant world, her father recently sent her the handbook How to Identify Wild Flowers. Asked about what she has learned from plants while living so close to nature, Daisy answers: ‘Well, for me, it's trying to learn their names, but also their interactions with their pollinators. And, well, taking the time to notice that they're not just plants – that they're connected to everything else. Plants rely on insects to reproduce, they rely on the bacteria in the soil to convert chemicals and nutrients. They are not “individuals”.

There has been a remarkable trend of exhibitions in the last year about nature in the art and design world. At the same time, we have to ask what happens next. How do we continue to build this movement? How do we get a more holistic outlook? Is the environmental emergency connected to social injustice? How do we make this global problem a shared fight against environmental degradation and inequality? I'm very worried that this topic will go out of fashion. Nature shouldn't be a fashion. We are part of it. We need it to live.’

Recently an artist living in London wrote to me that because of lockdown one could hear bird song in London again. Do you think people will learn something from this crisis, and will the birds stay? If they don’t stay, do you think people will really miss them?

I don't know. I think that humans are tricky animals. I noticed my Instagram filled with pictures of flowers and trees during the lockdown [this was before the BLM protests kicked off]; suddenly we’re taking much more notice of the natural world than normal. These privileged city dwellers who live in capital cities around the world are taking the time to slow down and look – escaping the screen, where possible. But what is really alarming is that when things start up again, how fast we will forget.

I was just reading about the postponement of the COP26 Climate Change Conference in Glasgow to next year. The IUCN World Conservation Congress 2020 has also been moved from June to January 2021. And the question is, will the environment fall off the agenda as we all rush back to rebuild our economies and rebuild our lives? I worry how environmental stories have fallen off the news agenda now when the movement was gaining traction; it's disappeared because of the pandemic, which is of course so important in the short-term. It seems we humans have a very short-term memory – we can keep hold of this momentary experience of clean air and bird song, and then we’ll go back to our old ways, because we need to.

I am really interested in the idea of ‘the shifting baseline’. If I think back to my childhood, I remember how the windscreen would be covered with dead insects after a trip on the motorway – this doesn't happen anymore. But that change is happening so slowly that we don't even notice it. That is the shifting baseline. Biodiversity is slowly (or in biological time – quickly) disappearing, but we do not notice it because we are are experiencing it in the short-term. During the lockdowns we had this moment, this glimpse of what the world would look like if we could turn the clock back – but not driven by choice, of course. I’m not confident that it's in our nature to prioritise that over short-term economic well-being – this drive for survival in the short-term maybe is human nature.

It seems we humans have a very short-term memory – we can keep hold of this momentary experience of clean air and bird song, and then we’ll go back to our old ways, because we need to.

Your PhD work at the Royal College of Art was titled Better. Did you find an answer as to why we always think that the future is going to be better than today? Why don’t we try to make today better, which is where we all live at the present moment? And who exactly defines what this ‘better’ future means?

‘What is better?’ – this is one of the questions I always ask. And then: ‘Whose “better” and who gets to decide?’ These are really important questions to ask whenever you hear this promise of better. Out in the street, you might see Papa John's promise of ‘Better Pizza’, or Total’s ‘Better energy’ advertised inside the plane gantry. What this ‘better energy’? It's oil. How is it better? How do you start to differentiate between these promises? The problem is that there are many dreams of ‘better’ and each of us have different ideas of what is better, and most importantly, our short-term actions don't necessarily match up with what we think is ‘better’ in the long-term. If I’m thirsty, I might buy that plastic bottle of water, even though it’s contrary to my long-term beliefs.

Humans are hopeful animals. I think it's in our nature to imagine that things could be better. Even if you think everything is terrible, that means you think it could be better – that's still an optimistic position. Even if you think it's unlikely that things are going to get better, to me, that is still optimistic: You still imagine that it could or should be otherwise. I'm trying to work out how do we, together, define the values of ‘better’? How do we sit down, think about and articulate shared values and goals that we can work towards? There are many people doing this – like climate-change campaigners, or those campaigning for social and racial justice. These are people getting together behind a set of values and defining what a better world looks like. What we really need as a species – and I don't know if it's possible but I remain hopeful – is to find ways to ensure our actions match the values that we say we support.

At the moment there are many discussions devoted to the possible ways how we, as humans, could restore the lost balance with the natural world. And thinking about our relationship with the natural world and our relationship with technology is a part of the problem. Because our relationship with technology actually is stronger now than our relationship with the natural world. Also, our senses are not trained to recognise the natural world anymore. At the same time, we are using technology – in our particular case, Zoom – but we are dreaming and talking about nature. It is in our DNA. Do you think it is possible to restore this connection that we’ve already partly lost?

I have been incredibly lucky during this lockdown to be in the countryside rather than in London, where I normally am. I'm spending much more time in nature. I'm just an hour outside London, but I'm doing things that I wouldn't normally do: noticing the passage of spring in individual species – not just looking at the cow parsley in the hedgerow, but noticing that, ‘Oh, it's now going to seed’. The plant is changing. I’ve walked past this plant every day for the last ten weeks. I don't think I've ever looked at nature in this way before, watching it every day, over time. Once this is over, I’d quite like to stay here and not go back to London!

I grew up in the countryside, so it's not like I haven’t spent time in the countryside, but having the time to look properly has really brought home how difficult it is to maintain a link to nature while living in the city. You can't look at it so intimately unless you have a garden or a place to observe it carefully in the inner city. So, yes, it's possible to change people and our relationships even in small but profound ways. But at the same time, lots of other things have to change. We need to change what we have accepted. Are you willing to go with less, to experience more of the natural world? Or demand the right to more? Are you willing to fight for the natural world to protect it; so that it is there for us all to enjoy? These are decisions we have to make.

This sudden awakening to the problems of climate change and biodiversity collapse feel like new problems for us in the developed world, but there are many peoples around the world and indigenous communities who've been living with this reality for a much longer time, feeling this loss, the crisis created by colonialism and modernity.

What I dream of, that is, my idea of ‘better’ is that we learn quickly. We can't live without other species and we know that, because we eat food and we drink water and we live on a planet. But for some reason, many of our lives have become distant from that. The burden of exceptionalism is even greater when you live in a city and you have no other way – apart from a few trees, a few pigeons, and a few rats (maybe a lot of rats) – to commune with nature. Then there’s very little first-hand evidence that you're not alone or special as a species. That’s a really weird situation.

I’ve been here alone with my partner, so my days are me and trees and insects and birds and then images of people I interact with online. That shift is strange: I experience only one other human in the flesh, and everyone else is a picture or non-human species. That's been a strange and wonderful thing, amidst all of this tragedy. And this is just the English countryside; it’s not a tropical jungle! So, I feel exceptional as a human in a different way now: the odd one out, but not especially interesting.

All your works are somehow related to nature. Can we humans, being a part of nature, ever understand something as complicated as nature? Or are we just scratching the surface, seeing as this situation with the pandemic has also shown us that science has limits and our understanding of nature has limits?

In a way, this is supernatural. And by ‘super-’, I mean it’s a very natural situation. A virus has jumped from one species to another species, which happens to be us. It's the story of the evolution of a virus and its adaptation. It is the ultimate biological experience. It shatters the idea that humans can control the world or that science can tell us everything. Science can tell us a lot – the speed of discovery about this virus is extraordinary. Imagine one hundred years ago, when the flu pandemic was coming our way. But this situation simply reminds me that I'm just a piece of biology. That I'm vulnerable like any other animal. It's super-natural. But what is also scary is that the story of engineering and the story of science is also a story of control. Yet, the reality is we do not have control of our destinies, and governments are struggling to find control.

The story of engineering and the story of science is also a story of control.

You’ve done many research projects related to artificial intelligence (AI). AI tools can be used for good, but at the same time, they can be used in a detrimental way as well. How can we keep this balance? What are the tricky points when working with AI?

I don't know. I'm struggling to grow tomatoes at the moment! (laughs).

Installation view of Resurrecting the Sublime at Better Nature, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, 2019. ‘Leucadendron grandiflorum (Salisb.) R. Br.’ (smell diffusion hood, granite boulder, animation) Photograph © Vitra Design Museum, Bettina Matthiesen.

For me, the biggest problem working with AI is how seductive it is. Machine Auguries (2019), where we artificially rebuilt the bird dawn chorus using machine learning, was the first time I properly used AI in a project. Previously my work had been about synthetic biology, and until the smell project Resurrecting the Sublime (2019) with Sissel Tolaas [smell researcher and artist – ed.] and Christina Agapakis [Creative Director of the biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks – ed.], I hadn't actually used synthetic biology in a project. I was enmeshed in the field, working with the engineers and scientists, but I was making work about the technology or reflecting on the technology. Resurrecting the Sublime and Machine Auguries were the first projects where I used the technology – and in innovative ways – to make critical work.

The biggest problem working with AI is how seductive it is.

What's difficult ethically, as a practitioner, is to critique technology when using and furthering it. In Machine Auguries we made headway in the field of deepfakes with sound. I'm worried about the impact of deepfakes, and yet I made a work that may have helped contribute (just a little) to the further development of that technology. I worked with Faculty, a London-based AI company and a leading researcher into AI-generated deepfakes of humans and ways to combat their misuse. We were doing scientific research for the project. And that's what's so difficult – it's seductive. It's amazing to hear a machine sing like a bird. Dr. Przemeck Witaszczyk, a machine learning expert supported by Faculty, joined us in the studio for the summer. It was just extraordinary to see how each day he got closer to making birdsong through AI. But it's also terrifying. Making the work hopefully creates reflection and brings it to people's attention. But the difficulty is that it is seductive. You’re thinking, ‘This is amazing’, but you need to step out and ask – ‘What is this?’ For me, learning more about this technology helps me understand its limitations and its possibilities better, and then helps me to bring attention to those limitations or the problems it raises.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. Machine Auguries, 2019. Installation shot from 24/7 exhibition at Somerset House, London, open 31 Oct 2019 – 23 Feb 2020. Commissioned by Somerset House and A/D/O by MINI. With additional support from Faculty and The Adonyeva Foundation / 2019. / Photo: Luke Andrew Walker for A/D/O

To what extent are we willing to turn our bodies into living machines for the promise of sustainability and profit? How can we escape being framed into becoming ‘economic robots’, or will AI push us even deeper into that?

I'm scared. I don't think that we have social control over the situation. The responsibility is being left to special interests. I was reading the news about China this morning that said that the health monitoring app being used for the coronavirus is going to become a permanent thing to bring wellness to Chinese society. That's terrifying to me – the infringement on personal liberties and privacy without debate. The mobile telephone is a prime example of how our actions are traced on adaily basis. The promise of making our lives better is made into an easy trade-off for those liberties.

A few years ago I was at a conference where Kent Redford, a conservationist, showed a statistic comparing the cost, I think, to preserve all biodiversity compared to how much the US spends on ice cream annually. And yes, the ice cream spending is higher that the amount necessary to solve a planetary problem. That is one of the best examples of our value system. We say one thing – and we mean it – but we do something else. We easily give up what we really value for the fast seduction of these technologies, or food, or whatever it is.

The mobile telephone is a prime example of how our actions are traced on a daily basis. The promise of making our lives better is made into an easy trade-off for those liberties.

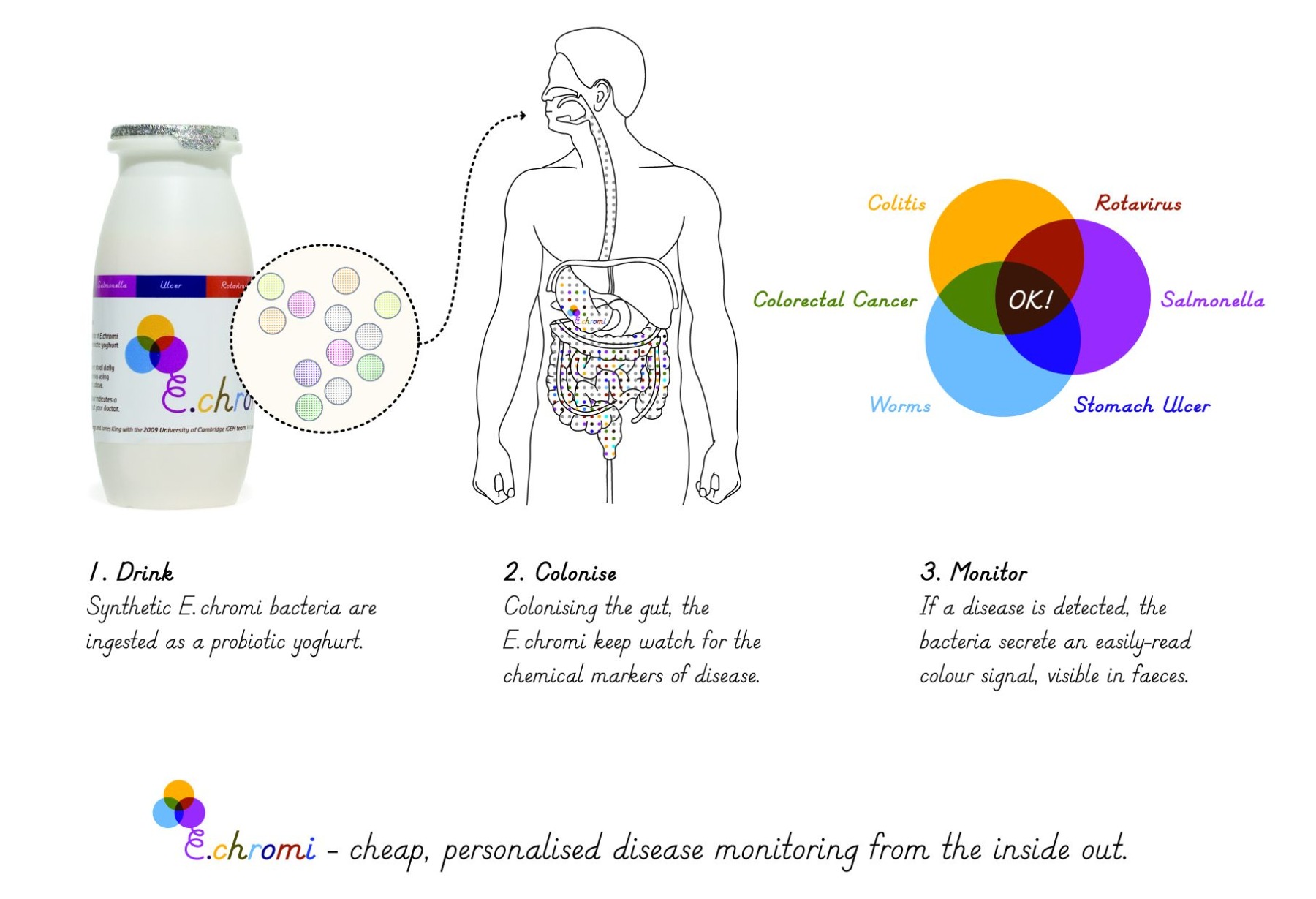

In your projects you use design and art to question science, human actions, etc. For example, E. chromi: Living Colour from Bacteria (2009), a project in which you explored the different agendas that could shape the use of E. coli, and, thus, our everyday lives. Could this be called better medicine, or is it internal surveillance? In some way it closely correlates with current surveillance discussions that have emerged due to the pandemic. What are the main lessons you learned through this project?

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & James King, with the University of Cambridge 2009 iGEM Team. 2009. The E. chromi Scatalog. Photo: Åsa Johannesson

James King, my collaborator on that project, and I were aware of the surveillance issues, so that project had a timeline over the century attached to the ideas we generated. We made it with seven students from Cambridge University who were genetically engineering bacteria to secrete a variety of coloured pigments visible to the naked eye for a student competition called iGEM, or the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition. We worked with the students to think about the implications of what they were doing while they developed the technology in the lab. We wanted to explore the different agendas that could shape the use of a foundational technology, and in turn, our everyday lives. We imagined a future where we’d drink engineered bacteria in yoghurt, which would then colonise our gut, keeping watch for the chemical markers of different diseases. If a signal was detected, the bacteria would produce an easy-to-read warning by colouring your poo. What would this mean for healthcare? What would it mean for privacy if a computer was biological? The Scatalog, as we called this briefcase of poo, was something we made after the workshop to take to the competition and talk to scientists about the technology and ask these questions of them. We set this fiction around 2039, but it became a goal for synthetic biologists and engineered probiotics are already being tested. Real technologies that detect biological markers in your body could be used as surveillance tools. To me that is worrying. Who owns these technologies? Would we even know if we were exposed to the technology? That's a new set of issues that biotech presents.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & James King, with the University of Cambridge 2009 iGEM Team. 2009. System diagram for the E. chromi Scatalog

Real technologies that detect biological markers in your body could be used as surveillance tools. To me that is worrying. Who owns these technologies?

There is on-going discussion between environmentalists who are focused on how to turn back the clock and preserve natural biodiversity, and scientists who want to use synthetic biology to make nature ‘better’. How sustainable and how environmentally friendly is synthetic biology? Do you see synthetic biology as a tool that could really help the natural environment, or is it more of a tool that could improve the economic interests of humanity?

My interest in synthetic biology taught me a lot about how a field of science and technology is built. And how power emerges in a field. I got involved in 2008, when the field was about eight years old. The first seminal paper about synthetic biology, by Drew Endy and Adam Arkin, proposed standardising DNA into parts. It was published in 1999. Now we're looking at a 20-year-old field that's very established. Synthetic biology is a kind of genetic engineering, but it has a certain set of values that are different: the core is that engineers can now program DNA, whereas (according to the synthetic biologists) the ‘old-fashioned genetic engineers’ were simply tinkering, not able to predict what would work because biology is so complex. This ideology, now aided by AI and machine learning, means things have moved forward very fast. Synthetic biology was a fascinating training ground for me. For example, I learned much more about genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which since the 1990s had often been projected as something to be wary of. But I began to understand why it's so much more complex than that. Synthetic biology, like any technology, is neither good nor bad. It depends on who is using it and for what reason. In the battle against COVID-19, synthetic biology is an incredible tool enabling diagnostic tests and vaccines. But there are other applications that may be less desirable. For example, I'm not crazy about engineering humans, which synthetic biology could also be used for. But it just shows how complex technologies have become. And that's been really useful for me to kind of set up a way of thinking about technology. Who is coming up with the visions for what it should be? And who gets to decide?

Synthetic biology, like any technology, is neither good nor bad. It depends on who is using it and for what reason.

How did you become interested in this subject? How did your involvement start?

I was training to be an architect, but I went off on my own path and ended up in the incredible Design Interactions master's program at the Royal College of Art in 2007, led by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. My interest in synthetic biology started when my classmate, the artist Sascha Pohflepp (who very sadly died last year), was in Berlin over Christmas 2007. He went to the Chaos Computer Club where Drew Endy, a bioengineer then at MIT, was giving a talk. Sascha came back and told me: ‘You won't believe what I heard. You're going to love this’.

I was already doing projects on genetics. But as I learned more about synthetic biology, I was fascinated by these ideological engineers coming in and saying, ‘We can control biology’. And the amazing thing is that students were doing this too. Student biologists were making bacteria that went dark like photo film, or bacteria that could switch on and off. There was something about this mixture of fear and excitement I experienced; the biological shock that they were making things out of the same stuff that I was made of, and controlling them. Making machines out of biology – it caught my imagination.

Now you are also closely connected to the art world. Is science the tool that helps us to understand the world, or is it perhaps art that in some way helps us to do so? Or maybe it is a collaboration between the two? After all, your work also is a collaborative process between different disciplines.

It's a wonderful question, really beautifully put. I think science helps us understand the world. I came across this quote recently (but I can’t remember by whom!), that ‘science makes visible the invisible’. And sometimes art can do the same thing. To bring things to our attention, which otherwise we can't see. I really enjoy talking to scientists because they just know all this incredible stuff about stuff I don't know about. That's just absolutely magic! The natural world is so extraordinary. And the opportunity to talk to someone who knows something amazing about how a bee finds a flower is mind blowing. Or how much semen does a southern right whale produce? A gallon! And the whale does this because it's the selected evolutionary strategy for mating if you're a southern right whale. Talking to scientists is such a privilege and highlight of my practice.

Increasingly, my work is taking an environmental standpoint, but I always try to work with scientists. I work hard to gain the scientists’ and engineers’ trust about what I am doing. These works are collaborative. But I’ve also managed to gain a bit of a reputation as a troublemaker through them in synthetic biology. I felt I was getting into trouble working in a field of technoscience, asking questions and making work where maybe my position wasn't so clear to outsiders, but the work was intended to be provocative to an audience within the science. I was reflecting what I saw back at them and asking them for their views, and trying to initiate discussion within the field. There has been a disdain for SciArt or art/science in the fine art world in the past. I hate all these labels. Basically, I make work about the natural world, often using technologies that are the most unnatural – technologies that try to simulate the natural world. By using them, I am trying to understand why humans make these technologies and why we don't just look at the natural world. The whole thing gets quite crazy... then I look at my tomatoes that aren’t growing. And I think: I don't understand why we have all these technologies and I can't make nature do what I want it to do (laughs).

There has been a disdain for SciArt or art/science in the fine art world in the past. I hate all these labels.

Look at the problem of colony collapse in bees. We don't understand why it’s happening. In the meantime, we’re still pumping out industrial pesticides, making loads of noise at all kinds of frequencies. And all these things affect other species. But we value those technologies perhaps more than these other species – until we get to the point where we're stuck. We may then have to invent new technologies to replace the biology that was already doing that thing.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. Simulation shots, The Wilding of Mars, 2019.

Last year you made the digital work The Wilding of Mars. Humanity has learned quite harsh lessons from the colonisation period. And we’re still seeing its impact, such as with sugar, for example, and monocultures. But it seems that humans don't change – the idea of colonialism is still alive. Why? Do we really need to adapt to live on Mars? Wouldn ’t it be better to take care of our own planet first?

That’s the question we should be asking. The Wilding of Mars was commissioned by the Design Museum in London for the exhibition Moving to Mars. When they started preparing the show, the curator, Alex Newson, asked me to propose a work. I said: I hate Mars; it's beautiful, and that's fine with me, but that's enough. I'm not pro colonising Mars, so it would be difficult for me to make something about that. And he said: No, that's fine. It can be critical. It just has to be optimistic. And it has to be family-friendly, so it can’t be a terrible dystopia. I thought that was the best brief to try to solve, because it has everything. I proposed building a simulation of seeding Mars with biology, but with humans excluded. No information is given how these plants get to Mars; all that happens is you watch a one-hour time lapse where a million years pass, and you see lichens and a few other species very slowly take over the landscape. I wanted it to be like a landscape painting – colonial vistas, slowly, slowly moving, evoking plant time not human time. We don't think of plants or trees ‘walking’, but they do – they're just not individually walking but moving as groups and over tens or hundreds of years, depending on the species. I wanted that to become evident in the experience – that you feel alienated as a human watching this thing. You don't belong. You can only watch. And I’m conscious that it’s a colonial action if there is indigenous life on Mars – sending (our) alien species there could extinguish indigenous ones. It still is a violent project. It was my intention to make this sort of uncertainty. Is this a good idea? The main questions I wanted the audience to ask themselves is – Why would we send humans? And why don’t we look after Earth rather than fantasize about a back-up?

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. Simulation shots, The Wilding of Mars, 2019.

In the 19th century, American amateur astronomer and businessman Percival Lowell spread the rumor that there were canals on Mars built by a civilisation trying to combat climate change. He misinterpreted the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who had identified strange lines or channels. It turned out that they were a distortion effect from his telescope. Lowell was actually echoing then-contemporary concerns about ecosystem destruction and desertification already happening on Earth due to colonial expansion and extractivism. He talked about ‘Earth going the way of Mars’. I wanted to reflect some of those concerns.

If there is indigenous life on Mars – sending (our) alien species there could extinguish indigenous ones. It still is a violent project.

In your work you question not only Mars and other things, but also the essence of design, reminding us that design is very much part of our material, capitalist society. For example, the profession of industrial designer was a product of the Great Depression in America as it was actually born from economical and political interests. Design was proposed as an economic strategy to stimulate people to consume their way out of crisis. In this complex world that we are living in now, what do you think is the designer’s main task, and what is the role of design today?

I have a really strong relationship with the design community. I was trained in design. I am really fascinated by why humans design. Why do we make stuff? Why do we make so much bad stuff? And when the stuff is good, what makes it good?

I studied architecture and I had a very fine undergraduate grounding at Cambridge in the history and theory of all Western architecture, which is a very biased view of architecture, of course. And then when I went to study design, I chose to study a strange form of design, critical design. When I started, I asked Anthony Dunne what books I should read about the history of design; he said there aren't very many – we have to write them! I had this sudden sense, having been burdened by the history of architecture, of something fresh and new in thinking about design. Design, as a profession as we know it, came out of the Industrial Revolution, when factory owners needed a way to make their product look different from that other factory's identical one. And design became enmeshed in capitalism. After the Great Depression, design became even more about the new and about creating demand to stimulate the economy. But there are lots of other kinds of design. You know, if you make a blanket or a knitted scarf, or create a trap to capture water from fog – that's all design. But it's just not sold in the same way. I'm excited about design that takes the optimistic spirit of creating something to make a better world. But that is very reflective – whose is better? That is why I am excited about design practices like Formafantasma or Faber Futures, these emerging practices that are looking at that question of what or whose is better and the values around design...rather than just producing a chair that may be beautiful, but isn't contributing more than just aesthetic development. I'm also for the aesthetic; I like beautiful things. And I think that's part of the contradiction, the excitement of being a contradictory human animal.

But do you, as a human animal, agree that producing less is a core value?

Definitely. I don't see any way around that. You can produce one million paper things instead of one million plastic things, but you're still cutting down trees to do that. And by cutting down those trees, you’re probably growing them in an unsustainable monoculture that isn't supporting a biodiverse forest environment. If you can plant your forest farm in a different way, then maybe it's fine. But overall, we can all do more with less. We just don't need all these things. That makes it hard for the young designer who says, well, I want to become a designer. And then they realise that's really unethical. So how do you make new things that don't need to be bought as often? That's a hard question if you need to find a job. That's about designing systemic change.

What is exciting about design is that there are loads of ways that designers can think about systemic change. I'm not talking about service design because that is often in the service of capitalism. I mean more radical designers, like the ones of the 1960s, who worked as activists. I think there are some amazing examples of those kinds of practitioners emerging.

Installation view of Resurrecting the Sublime at Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne, March 2019. Each vitrine is filled with the smell of an extinct flower. 2019. / Credit: Christina Agapakis of Ginkgo Bioworks, Inc., Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & Sissel Tolaas, with support from IFF Inc. / © Pierre Grasset

Talking about your Resurrecting the Sublime project, I was wondering if we could really bring back the smell of an extinct flower. And, why do we need this? What could we learn from it?

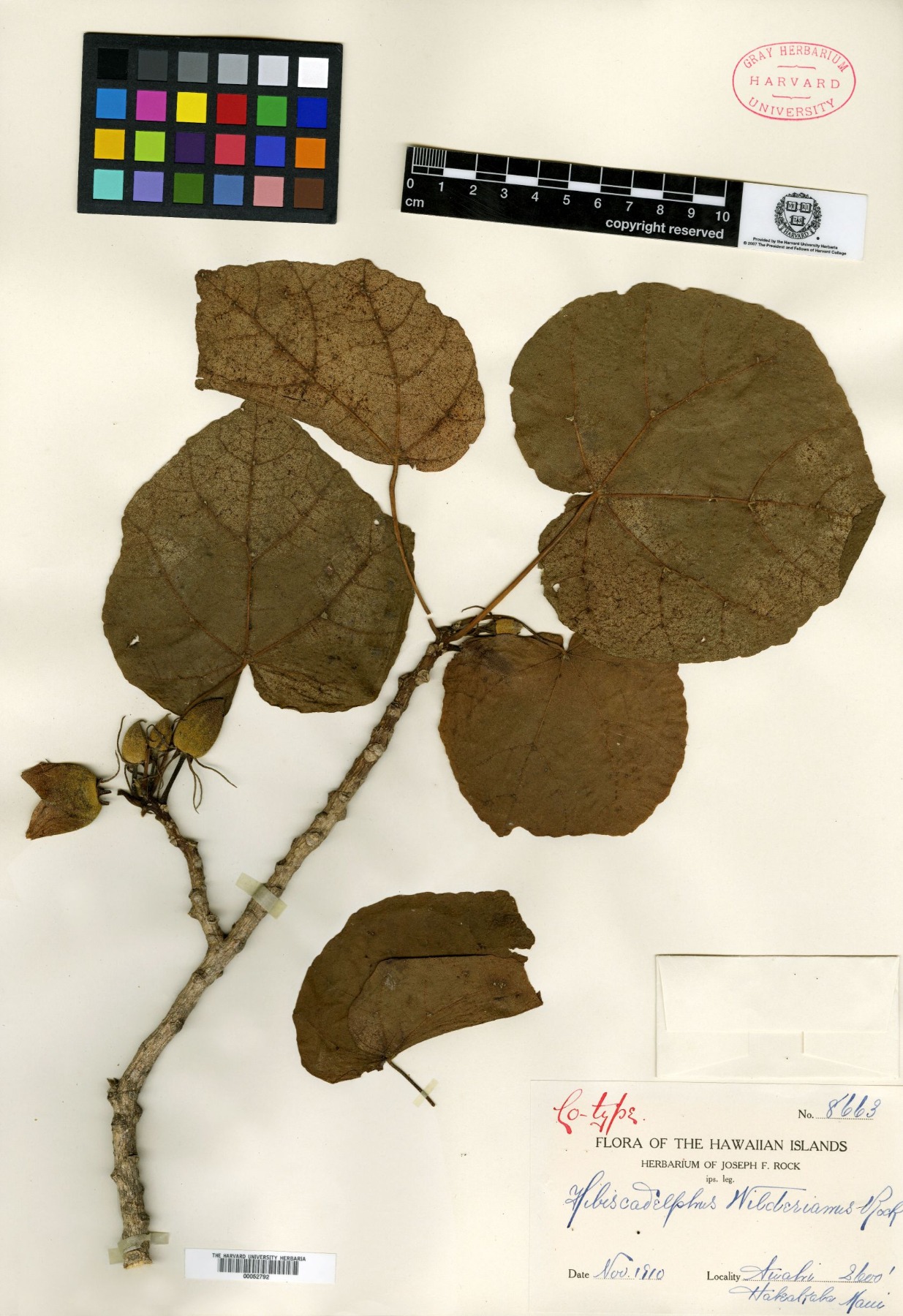

That is a very good question. Do we need it? No. Can we do it? No. So can we bring it back? Well, no, not at the moment. Resurrecting the Sublime is a bit like looking at a painting through a dirty window. All three flower specimens that Christina (Agapakis) took samples from were from the Harvard University Herbaria. The Ginkgo team extracted DNA from these samples, and through its analysis, they produced a list of smell molecules that each plant may have produced. Sissel (Tolaas) used her expertise to reconstruct the flowers’ smells in her lab using identical or comparative smell molecules. But what you're getting is a bit like trying to build a rhino from its DNA: it’s not the whole story.

Installation view of Resurrecting the Sublime at Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne, March 2019. Each vitrine is filled with the smell of an extinct flower. 2019. / Credit: Christina Agapakis of Ginkgo Bioworks, Inc., Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & Sissel Tolaas, with support from IFF Inc. / © Pierre Grasset

I was speaking two weeks ago with the director of the National Tropical Botanical Gardens in Hawaii; one of our flowers was the Hawaiian flower Hibiscadelphus wilderianus, which was indigenous to ancient lava fields on the southern slopes of mount Haleakalā. That landscape was decimated by colonial cattle racing, and the last tree was found dying in 1912. And we remade its smell. The head of the gardens said to me, did you know that Hibiscadelphus – there are related species that aren’t extinct – don’t smell? (Laughs) I think that’s because this particular plant was pollinated by birds, not by insects, so the plant has the genes that can instruct smelly molecules to be produced, but those genes are not necessarily turned on. That's something that the science was not able to distinguish from the DNA samples – which genes are turned on and which are turned off. I love that. You can do this incredible science and it is absolutely amazing what Ginkgo Bioworks has managed, but it doesn't give you the contextual clues. It doesn't tell you the full story of how a flower is not just a flower, it's an organism in the landscape, in an environment, and part of a complex ecosystem. Maybe one day we will have the technology where you could run the DNA and rebuild the animal or the plant. Without the original environment, unless we recreate the environments of these organisms, is it necessary? Is it ethical? Is it better to preserve what exists now? These are all the questions that I'm asking in this project and in another, called The Substitute, about the near-extinct northern white rhino.

Video still from The Substitute, 2019. Credit: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. Visualisation/animation by The Mill.

You were asking – can we do it? Do we need it? Well, do we need anything? For me, the smell of an extinct flower, even if it's not its true smell, is a moment of the sublime. It's like a time machine – even if it's taking you to the wrong place, it's an extraordinary experience. That's hopefully a purpose of it. If it has any utility, it's enabling people to connect to something which they would never have thought about otherwise. To think about the loss of something so obscure. And, OK, if we don't care about rhinos, who are big and charismatic, do we care about an obscure flower that grew on one hill? People do seem to get emotional when they experience the work, and that's really beautiful because then maybe they’ll look at another flower that is living and take more care.

For me, the smell of an extinct flower, even if it's not its true smell, is a moment of the sublime. It's like a time machine – even if it's taking you to the wrong place, it's an extraordinary experience.

Dried specimen of Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock, collected on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakalā, Maui, Hawaii, in 1910. / 2018. / Credit: Gray Herbarium of Harvard University / © Gray Herbarium of Harvard University

To return to the beginning of our conversation, how do we make sure that we don’t rebuild the same world when the pandemic will be over? Because this is what most of us want – to get back to normal as soon as possible...

I wish I knew the answer because that's the question everyone's asking! I don't know if we can build something different. I would like to hope so.

What we're all doing now is trying to cope. It's not easy, especially for those of us still in lockdown, and our experiences of lockdown are so different, and I know I’m extremely fortunate not having to travel for work and be exposed to risk. For each company or country that's having to rebuild, there's an opportunity to rebuild differently and with a different set of values. But in a moment of desperation, how many will do that while trying to survive in the short-term?

I can make personal choices about what I'll do differently. I want to travel less. I'm happy that finally you can give a lecture on Zoom – a few months ago, that same one-hour lecture meant flying to share your work. But I'm worried that we will just go back to the same thing, or worse – with even greater injustice and destruction of natural resources. That's a pessimistic answer from someone who has spent so much time thinking about what is ‘better’. We have to choose to be optimistic – through the choices we make, through our actions and through what we fight for.